Tl;dr the people who support a political figure who says, “I am so committed to the Real People that I will violate all legal and moral norms to enact my policies” always end up regretting it. Trump is very precedented, and it’s never worked out well.

I once had an unfortunate disagreement with a colleague whose work I so very, very much admire and have always supported. It came about because they kept saying that Trump and his actions are “unprecedented.” They were saying this for good reasons—wanting to mobilize outrage about Trump—but it is a historical claim, and, as such, it’s false. More important, it’s rhetorically (but understandably) misguided.

I think I came across as a pedant, crank, or someone who disliked their work. In reverse order, I love their work, and I am a crank and pedant, but, as it happens, when it comes to my insisting we not talk about Trump as unprecedented, I am neither.

His supporters believe he is unprecedented, and that’s one of the main reasons they support him. And they deflect any consideration of the precedents, as well as any criticism of him.

A lot of criticism of Trump has to do with who he is, and that kind of criticism helps him. All the evidence is that he is a corrupt, dishonest, racist, fiscally incompetent, and dishonest man who regularly sexually assaulted women, and who advocated insurrection. But there’s no point in emphasizing any of that when talking to his base because they agree that he is that person and did those things. They support him because he is a racist, corrupt, dishonest, rich person who gropes women. Most of them like that he is that person. They want to be him.

People who aren’t his base support him because they believe that they will benefit from the policies he’ll enact, especially “freeing” business owners and rich people from rules, restrictions, and taxes.

And there are people who will vote for him just because they have been trained to hate the hobgoblin of “liberals” by years of demagoguery. Some of them aren’t wild about Trump, and some have become wild about him because of the criticism. That kind of support is strengthened by the way that media and some scholars frame our vexed and complicated world of policy commitments as actually a third-rate reality show of a fight between “liberals” and “conservatives.” The single-axis model of policy affiliation depoliticizes policy argument, but that’s a book (which may come out fairly soon, fingers crossed).

Here’s the important point: just because that’s how the media frames something, and it’s possible to find supporting data, that doesn’t mean the frame is either accurate or useful. The media frames questions about birth control in terms of pro- or anti-abortion. It framed questions about the Iraq invasion as pro- or anti-war. Both of those policy disagreements are and were better served by acknowledging a a spectrum, rather than a single-axis continuum or binary.

The media frames all questions in terms of two identities at war (“left v. right”). To the extent to which media–even if they identify as “left”–frame issues in terms of identity, they help Trump.

There are a lot of reasons that people support Trump. People who rely on Fox News, the manosphere, Newsmax, for their information would vote for a cold turd as long as they were told voting for that turd would piss off “the woke mob.” Second, chiliastic fundagelicals love his aggressive actions in regard to Israel because they want nuclear war there–they believe it will reduce the number of Jews to 40k who will be converted, and thereby bring about Jesus’ reign on earth. That many Jews are choosing to support Trump because of his advocating policies that increase the likelihood of nuclear war in that region is just really frustrating. Third, descendants of immigrants pull up the ladder behind them. Unhappily, this has always been the case—the people most hostile to a new group of immigrants is the most recent group of immigrants. Fourth, toxic populism.

I think the first three are fairly clear, so I’ll emphasize the last.

Populism says that our world is not complicated, but actually a zero-sum battle between an elite and the real people. It says that we don’t have reasonable and legitimate disagreements about policies. It says that the correct course of action is obvious to all real Americans/Christians/workers/conservatives/whatevs. [1]

Commitment to a populist leader is generally irrational. Populist leaders say there is a real us, and that all our problems are caused by Them. They say that we can solve all our problems by fanatical commitment to the in-group, and refusing to listen to any criticisms of the in-group. The first move of toxic populists is to ensure their base dismisses as “biased” any criticism of them. They do so by demonizing (they’re evil), irrationalizing (they’re motivated by feelings, but we’re motivated by reason), and pathologizing (they’re lazy, criminal, corrupt) any source that is not fanatically committed to the leader/group.

Trump is a toxic populist.

The proof is that, if you say this to any of his supporters, and give the definition of a toxic populist, they won’t engage your argument.

Their first move will be whaddaboutism, their second will be deflecting the definition on the grounds that, since it applies to Trump, it must be “biased” (they’ll probably say “bias”), their third will either be harassing you (they like signing you up for Ashley Madison) or blocking you.

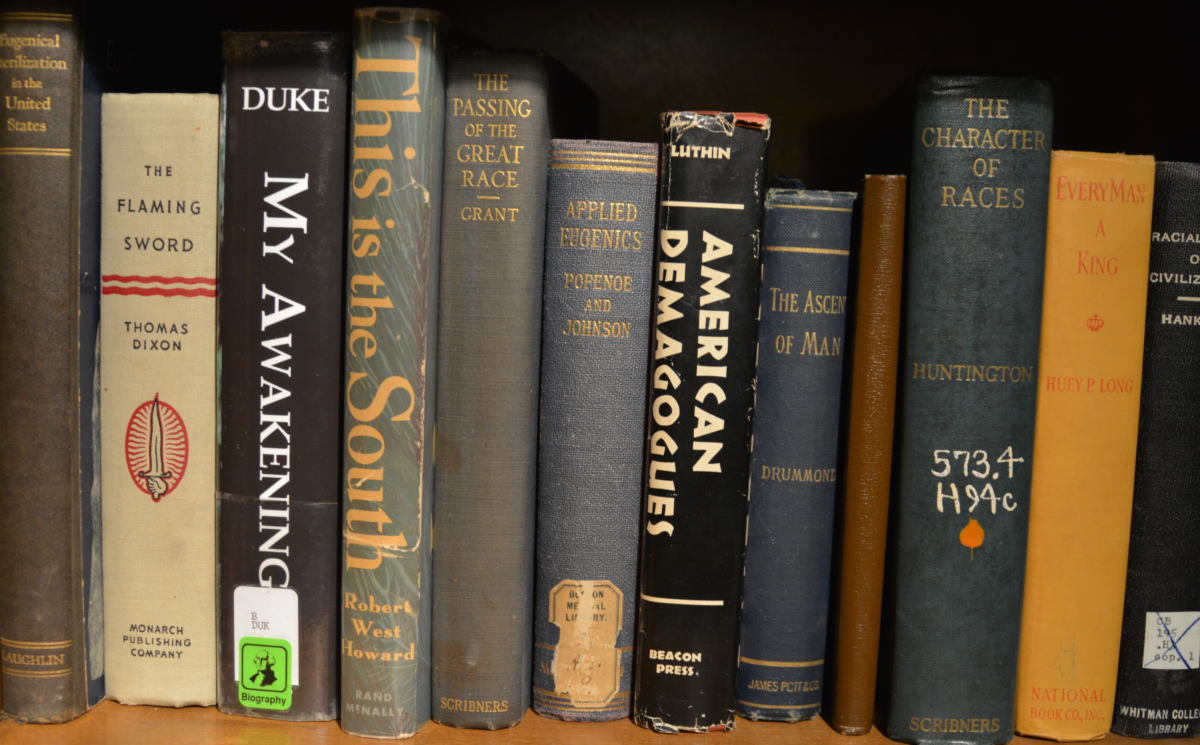

Claiming that Trump is unprecedented confirms his supporters’ belief that there is no already existing evidence that what he wants to do is politically, ethically, and economically disastrous. It enables them to deflect comparison to Castro, Chavez, Erdogan, Franco, Hitler, Jackson, Mussolini, Putin. Claiming that Trump is unprecedented saves them from the rhetorical responsibility of showing that supporting someone like Trump has worked out well. (Narrator: it hasn’t, especially for the working class, but even for plutocrats.)

Not all Trump supporters are the same, but the narrative that he is unprecedented enables every one of them to keep from thinking about the long-term consequences of their support. But, as I said, he’s following a playbook. It isn’t restricted to “right-wing” (I hate that term) leaders. What’s wrong with Trump isn’t about left v. right. It’s about whether a political leader values and honors democratic and legal norms or argues that he (almost always he) shouldn’t be held to them because reasons. And a leader who has made that argument has never worked out well.

Many of his supporters, like people who have supported authoritarian governments in Central Europe, are wealthy people who believe that they will profit from an authoritarian anti-socialist government. In Russia, they supported Putin, and they were wrong, as shown by what Putin did to the economy, and by the number of plutocrats who fell out of windows and landed on bullets. Paradoxically, capitalism requires innovation, and there isn’t much of that in an authoritarian culture. Authoritarian cultures/governments that have been profitable have done so by stealing ideas and innovations from democratic ones (e.g., printing or weaving).

But, and this is the important point, there are other examples of times when the people with a lot of monetary power backed a charismatic leader who was openly advocating an authoritarian government, and it didn’t work out well for them. There are precedents, and they show that charismatic leadership is actually a really bad way to run an organization, let alone a country.

The question Trump supporters should be asked is: when has support of this kind of political figure worked out well?

And that is the only aspect of Trump that is unprecedented.

[1] For a long time, I was averse to calling this “us v. them” false way of thinking about politics “populism.” I thought it should be called “toxic populism.” But, that train has left the station. Still and all, I’d argue that there is a difference between “our current political situation hurts these groups that don’t have a lot of political power” [what I think of a kind of populism—trying to worry about the ramifications of our policies on people not in power] and the binary thinking of toxic populism (our complicated political situation is actually a simple binary between people who are good/honest/real/authentic and Them). The best short book on populism is Jan-Werner Müller’s What is Populism. The best thorough work is the Oxford Handbook on Populism.