Matt Grossman and David Hopkins, when talking about what they call “the ferocity of today’s political battles,“ point out that our political discourse isn’t primarily policy argumentation:

Democrats and Republicans not only attack each other for subscribing to misguided beliefs about optimal public policy but also regularly question each other’s motives, intelligence, and judgment; suggest their opponents are not making good-faith arguments; and accuse each other of merely doing the bidding of special interests or pandering to popular prejudices. (329)

To the extent that we talk policy, it’s about what advocating or critiquing the policy means about the identity of the rhetor—we don’t argue about whether policies are racist, but whether rhetors are. The foundational cultural logic of too much of our public discourse presumes that all questions can be reduced to the question of the motives of the rhetors, and that question can be settled by determining their in-group.

And I need to begin with an aside about what I’m not arguing in this paper since I’ve found this is such a fraught topic. In addition, and this is fundamental to our challenges as teachers—Arlie Kruglanski, Daniel Kahneman, and others have shown, we tend to reason syllogistically. That is, on meeting a new person, or even reading an argument, our first cognitive task is to categorize the person or argument—to put them in a social group, genre, political or philosophical affiliation. We decide what larger group they’re in, and they deduce that because they’re in That Group, they must believe These Things. They must believe the other things we assume are necessarily connected with being in That Group.

Since a large part of what I’m critiquing is the reduction of all political questions to in-group/out-group membership, it might sound as though I’m advocating some kind of neo-Habermasian public sphere of brains arguing with one another, and I’m not. A public sphere in which identity arguments were prohibited would be not only impossible, I suspect, but irrational—identities are relevant claims. I’m not objecting to arguments about or grounded in identity; I am saying that reducing all questions to ones of social group identity (in which each identity group is presumed to be homogeneous and perfectly constitutive) is vexed. It becomes actively damaging when that reduction is tied to the assumption that only one of those groups (an in-group) is constituted of people of intelligence and goodwill whose views are the only valid bases for public policy.

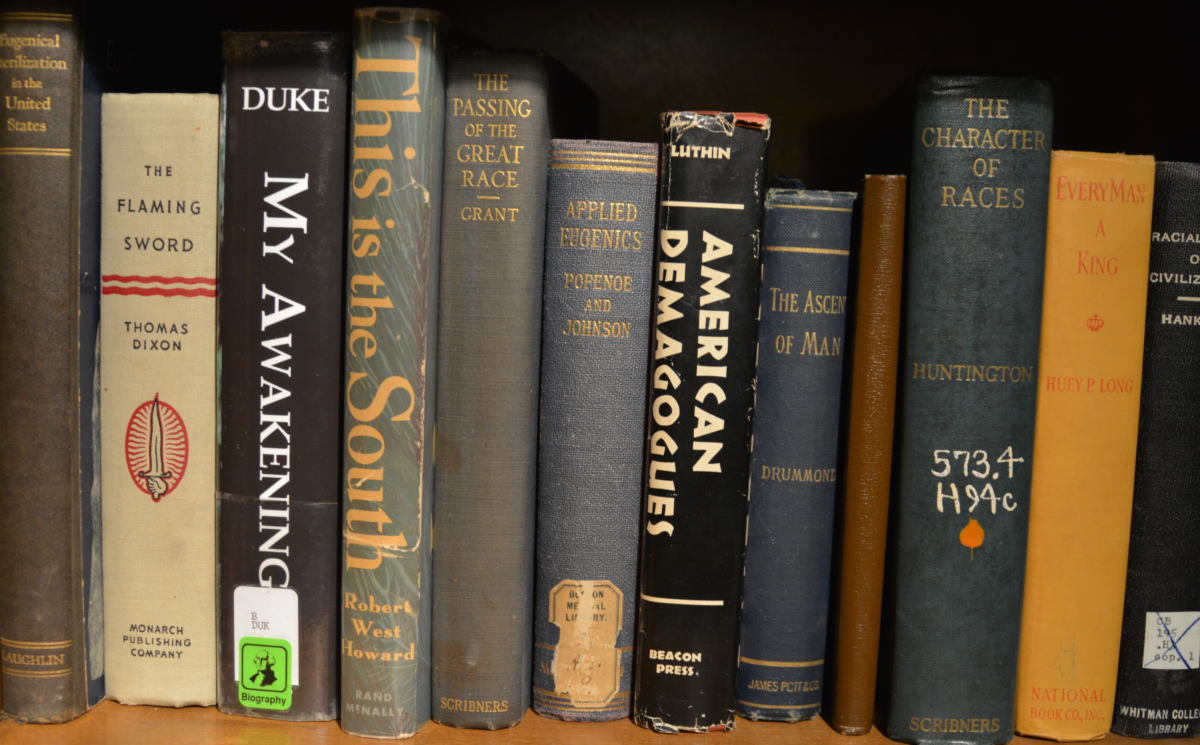

In other words, when the point of raising the question of identity is because we, as a community, are trying to hand deliberative power over to an individual (or individuals) who embody/ies that homogeneous Real American, Real Slaveholder, Real German, then we’re in a culture of demagoguery. There are other characteristic.

I’ve argued elsewhere that we’re in a culture of demagoguery, by which I mean that there are certain widely-shared premises about politics and public discourse:

-

- Every policy/political issue has a single right answer, and all other answers are wrong;

- That correct answer to any political question is obvious to people of good will and good judgment (that is, to good people);

- The in-group (us) is good;

- Therefore, anyone who disagrees with the in-group or tries to get a different policy passed isn’t just mistaken or coming from a different perspective or pointing out things it might be helpful for the in-group to know, but bad, and

- Deliberation and debate are unnecessary, and compromise is simply making a good policy less good.

- So, in a perfect world, all policy decisions would be made by the in-group or the person who best represents the in-group’s needs,

- And, therefore, the ideal political candidates are fanatically loyal to the in-group and will shut or shout down anyone who disagrees.

[By in-group, social psychologists don’t mean the group in power, but the social group of which one is a member. So, for some people, being a dog lover is an in-group, even (or especially) in the midst of a culture in which that identity is marginalized.]

This is not the conventional way of thinking about demagoguery—if you look at a dictionary, it will probably define demagoguery as speech by demagogues (in other words, it reduces the issue to one of identity—a demagogic move).

In common usage, demagoguery is often assumed to be obviously false speech that is completely emotional, untrue, and evidence-free on the part of bad people with bad motives.

That’s a useless definition for various reasons (including that it doesn’t even apply to many of the most notorious demagogues); it’s also actively harmful in that it impedes our ability to identify in-group demagoguery—that is, demagoguery on the part of people we like. And it does so because we can tell ourselves this isn’t demagoguery if:

-

- we think we are calm while reading the text, and the text (or rhetor) has a calm tone

- we believe the claims in the text are true

- the claims can be supported with evidence

- we believe the people making the argument are good people

- we believe they have good motives

One of the things I want to suggest in this talk is that teachers of writing are often unintentionally engaged in reaffirming the premises on which demagoguery operates, and we can do so in two general ways: first, by teaching criteria of “bad argumentation” (or demagoguery or propaganda or whatever devil term is in question) that don’t productively identity the problems of certain kinds of public discourse, thereby giving people a false sense of security—as in the above criteria. We can feel comfortable that we aren’t consuming or producing demagoguery when we are. Second, a lot of writing and especially argumentation textbook appeal to the rational/irrational split, assume a binary in epistemologies (so that one is either a naïve realist or relativist), require that students engage in motivism, and rely on a modernist formalism about what constitutes “good” writing.

For instance, if you look at the criteria for determining demagoguery, you can see the standards often advocated for a “good” argument.

If, as I’ll argue, that isn’t a helpful way to think about demagoguery, then the consequent way of teaching argumentation not only ends up reinforcing demagogic premises about public deliberation, but puts teachers in a really difficult place for talking productively about issues like bias and fairness.

There are other ways that we unintentionally get ourselves into a complicated situation:

-

- Teaching writing process as first coming up with the thesis and then doing research

- Teaching research as finding sources to support one’s point

- Teaching audience in terms of social groups (e.g., teachers, conservatives, women) and identities (as though those identities are necessarily connected to particular values and beliefs)

- Reinforcing the notion that rational and irrational are issues of logic versus emotion

- Teaching bias as something that can and should be determined by identity, and thereby encouraging motivism

It’s important to note is that the above criteria for assessing whether something is demagogic are useless insofar as they’re circular—demagoguery is what THEY do. And a community in which we’re all flinging the accusation of demagoguery like bricks over a wall isn’t one in which we’re going to come to good decisions. We’re still participating in public discourse on the basis of assuming that only our in-group is good and has legitimate policies.

This premise—that only the in-group has a legitimate political agenda—has various important premises and consequences:

-

- the notion that the true course of action is obvious to good-willed people comes from our cultural tendency to rely on naïve realism (a notion reinforced by public discourse that says the only two possible epistemologies are naïve realism or sloppy solipsistic/relativism);

- the rational/irrational split: that is, the notion that an argument is rational (unemotional, true, and supported with reasons) or irrational (emotional, untrue, and made by the out-group)

- the fundamental attribution error (the tendency to attribute different kinds of motives and behaviors on the basis of group membership)

For the next part of the talk, I’m going to go through each of those.

Naïve realism is both an epistemology and ontology—it presumes a Real world entirely external to human cognition or perception (so it’s a foundational ontology) AND that the unmediated perception of that world is easy.

In such an epistemology, the assumption is that we perceive things accurately and then distort those perceptions through the imposition of prejudice or bias. Thus, if you are biased, you can know, because you simply ask yourself if you distorted what you initially perceived—if you are not aware of any distortion, then you can’t possibly be biased.

It is a talking point in some media that you either believe this epistemology (that whether something is right or wrong, true or untrue, is immediately obvious to good people) or else you are a postmodernist, which is a devil term for a sloppy kind of solipsistic relativism—that all beliefs are equally true, there is no right and wrong, and no one has the right to judge anyone else. But those aren’t the only options.

Such a world implies that either there is one right answer to political issues or it’s just a question of what party manages to force its agenda on everyone else—neither of those epistemologies supports democratic deliberation. And neither is accurate for how most of us spend most of our days.

We rely heavily on science, for instance, which is grounded in a foundational ontology, but a skeptical epistemology (with various scientists at various points on a continuum of skepticism about human’s abilities to perceive accurately as individuals or communities, and another continuum about our ability to justify our beliefs—that is, to know whether we know).

So, one thing teachers can do is avoid the false binary of naïve realism or solipsistic relativism, and encourage students to see ourselves as in a place of more and less educated guesses—certainty is a question of degree, not a binary.

The next premise is complicated to explain, and it’s complicated largely because American teaching of argumentation has been unhappily oblivious to the field of argumentation theory.

In formal logic, one can determine whether an argument is logical purely internal by the internal moves. A good argument has certain forms. That works with formal logic, since the arguments are about p and q but, as even Aristotle pointed out, it doesn’t work when you get into the world of politics. Politics, like ethics, is a phronesis, not an episteme.

Informal logic relies on what is happening within a disagreement; it’s about context—the straw man fallacy, for instance, is the dumbing down of an opposition argument. To know if a rhetor has engaged in that fallacy, we have to know what the opposition argument is.

That’s important because it means that it isn’t possible to stay within an informational enclave and judge the rationality of an argument. Being a rational participant in public deliberation doesn’t mean being unemotional—that’s neither possible nor desirable—but it does mean actively seeking out and listening to the best versions of the opposition arguments. It means the opposite of what demagoguery tells us—stop listening to any argument the second you determine it’s an out-group argument—and it also means acknowledging that the out-group is varied enough that there are various arguments that might be made.

Once you start trying to find the best out-group arguments, you quickly determine that there are a lof of non-in-group groups. The whole in-group/out-group binary collapses. We have a tendency to homogenize the out-group, and to treat them as interchangeable, so if we can find one member of the out-group with a stupid argument, we attribute that argument to the whole group.

Rationality isn’t about emotionality or lack thereof; it’s about how an argument works in a disagreement, and it can come down to three rules: first, a rational argument is internally consistent (terms are used consistently, it appeals to premises consistently); second, whatever rules there are apply across groups; third, the issue is up for argument—participants can identify evidence or arguments that would cause them to change their minds. Rational argument is about taking on the responsibilities of argument, and those responsibilities apply equally across groups.

When we rely on in-group/out-group thinking, we apply responsibilities differently.

| Good behavior | Bad behavior | |

| In-group | Internal narratives of causality | External narratives of causality |

| Out-group | External narratives of causality | Internal narratives of causality |

The in-group always has the moral highground, even if doing something we condemn the out-group for doing: when the in-group behaves well, it’s because that’s who we essentially are. If the in-group behaves badly, we were forced, that’s an exception, it wasn’t a true in-group member.

But, if a member of the out-group does something bad, that bad behavior is a sign of their essentially bad nature, and that is the fundamental attribution error. And that’s the third factor that contributes to demagogic reasoning and discourse.

And these three factors—naïve realism, misunderstanding rationality, and the fundamental attribution error—contribute to very unhelpful ways of thinking about bias, precisely the ones that get teachers into complicated situations.

“Bias” is often assumed to be the necessary consequence of group identity—that is, having a particular group identity necessarily biases us in specific ways , and that makes sense in a culture of demagoguery—all arguments can be reduced to questions of identity because, in this world, it is assumed that identity is constitutive of belief, and that groups are essentially homogeneous.

As I said, demagoguery appeals to the unhappily common notion that the correct course of action is always obvious, even in politics, and that the in-group advocates that obviously correct course of action.

The only criticisms of the in group that is allowed in a culture of demagoguery are to say that members of the in group are not sufficiently passionate or fanatical about in group policy agenda, or have been allowing the outgroup to get away with too much.

Being willing to consider substantive criticism of the policies or premises of the in-group is proof that one is not loyal to the in-group—a member of an out-group, in other words. And, since out-group members have distorted perception, criticism of the in-group is, in and of itself, proof of “bias.”

In a culture of demagoguery, the very act of disagreeing demonstrates that one is too biased for one’s criticisms to be considered.

And, since, in a culture of demagoguery, the out-group is figured as demonic, even listening to an out-group member is risking contamination, so disagreement is itself a sign of the presence of evil that is to be crushed, rather than a point of view that might have value. Giorgio Agamben argues that in a state of exception, groups that claim to honor law do so through not-law; I’m suggesting that we might think about not-logic—that some groups claim that we are in such a state of exception that groups claim to be entirely logical by rejecting logic. It’s not-logic.

Since the premise of democratic deliberation is that disagreement benefits a community, and the premise of a college education is that it prepares students for effective participation in a democratic culture, teachers who want to promote the democratic values of empathy, fairness, and reasoned disagreement can find themselves in a fraught situation.

And it’s a situation about which everyone should be concerned.

We live in a culture in which it is only allowed to condemn them—we are supposed to be in such an existential crisis (the in-group is about to exterminated) that we should not allow in-group criticism. We are in Agamben’s state of exception, in which free speech is honored by silencing people who disagree.

One of the reasons that cultures of demagoguery tend to crash is that they cannot learn from their errors—because they can’t admit that they made errors. Think about German nationalists, none of whom would admit that fear-mongering about encirclement, belief in the redemptive power of war, racism, and a sense of entitlement to European hegemony all contributed to the tragedy that was World War I, and so they ratcheted up fear of encirclement, rhetoric about the redemptive power of war, racism, and assertions of entitlement to European hegemony, and made the same mistake again, with tragic world consequences.

Assuming that criticism of the in-group claims or policies signifies bias ensures that the in-group will keep making the same mistake over and over—it precludes argumentation about means and process. Hitler wasn’t just wrong as to whether Germany was entitled to European hegemony, survival of the fittest, and his incoherent racial policies, he was wrong as to how communities should make decisions—he was wrong about content and process.

As teachers, we aren’t just teaching content; we’re teaching process. But people often assume we’re teaching content—in an authoritarian model of teaching, the teacher pours knowledge into the head of students. We are trying to get students to understand that it’s about metacognition.

Students are inoculated to see us as teaching a sloppy relativism, and trying to force them to adhere to our political agenda—that is, a lot of students listen to media that always equates “out-group” and “biased” and that projects their kind of indoctrination onto everyone else. So, the message is that teachers, who are all Marxists, will force students to repeat Marxist talking points.

One way to try to move students to a more fair analysis of politics if for us to be very clear that we don’t equate “out-group” and “biased” by identifying some out-group texts as good, and some in-group texts as biased. We shouldn’t be engaged in demagoguery. We should model that the world isn’t in-group and out-group, but a lot of people with different perspectives.

There is another way that people reason from identity, and it’s very concerning for people who believe in democracy. A disturbing number of Americans believe that they represent true Americans, and that anyone with a different set of political concerns shouldn’t count. Thus people on various forms of government subsidy are outraged about other people on government subsidy, not because they’re hypocrites, but because they believe that their needs (and the needs of people like them) are legitimate because they embody true Americans. The Ur assumption is that there is a single identity of True American—if we could get people past that, everyone would benefit. But that’s a different talk.

So, government subsidies for corn is the government looking out for true Americans, but government subsidies for solar energy is pandering to special interests—because corn farmers are true Americans, and solar energy people are not. That’s in-group/out-group reasoning.

We need to teach a different way of reasoning.

I’m not advocating what is often called a “liberal” pedagogy, in which all positions offered are treated as equally valid, nor a liberatory pedagogy, in which positions the teacher considers oriented toward genuine critique are privileged, but a fair pedagogy, in which all positions are assessed on the basis of whether they engage the most informed and intelligent opposition positions. It is a classroom in which students have to be fair to opposition positions—that is, holding them to the same standards they hold the in-group arguments—and in which teachers do the same.

Does that mean that every class has to relitigate evolution, or the causes of the Civil War (if you think it wasn’t slavery, read the declarations of causes), or racism? No.

But it does mean that we either begin the class with an open premise that the conversation of the course will be within certain premises (a literature course about slave narratives can begin with the premise that slavery was bad, a physics course can begin with the premise that gravity is a thing) or we set up the parameters of the writing assignments such that students aren’t writing about something we aren’t willing to relitigate.

In other words, “open” assignments are just asking for trouble, and the resulting papers can’t possibly be assessed by the standards of rational-critical argumentation unless the workload is unethical.

“Open” assignment prompts assume one of two things: either the rationality of an argument is entirely internal to a text, or the teacher assessing the argument knows the entire sphere of argumentative possibilities.

The first is indefensible, and the second requires that someone be even more of a political geek than I am, or that the teacher do massive research for every paper. Or, the teacher is engaged in in-group/out-group thinking and believes that out-group arguments are pretty much all the same. Open assignments mean teachers have an extraordinary engagement in political discourse, an unethical workload, or are promoting demagoguery.

And, unless the teacher really does read all the arguments about all the issues, a teacher cannot assess the logic of an argument.

I’m sure I just alienated almost everyone in this room, but I’m going ahead with this argument, because I think it’s important.

A huge part of the problem in rhetoric and composition is that the most popular textbooks of argumentation are cheerfully uninformed by actual scholarship in argumentation theory. For a long time—such as at least since Aristotle—there have been people who have argued that logic operates differently in spheres of inherent uncertainty (such as politics and ethics) and those who insist that logic is universal (Plato appears to have been in this category, but there are arguments about that—after all, he did have Aristotle teaching rhetoric). Logical positivism tried to ground all discourse in formal logic—that is, the notion that a logical argument has a particular form, one that operates universally. So, a specific argument is logical or not regardless of context. The Anglo-analytic tradition treats formal logic as the true logic, and informal logic as just bad formal logic. That’s a fallacy.

Also, that way of approaching argument led to a binary—since it obviously doesn’t work when people are arguing politics, there was a sense of logic either being a dominating and normative smackdown that seemed to make all actual political arguments illogical, or (and therefore) the embrace of the logic of an argument being determined by audience reaction.

In the 1970s, scholars of argumentation made a move that is still not represented in argumentation textbooks: the logic of an argument is determined by its place in a particular kind of conversation.

Were argumentation textbooks informed by argumentation theory, then teachers would asses arguments on this basis:

-

- Freedom rule

Parties must not prevent each other from advancing standpoints or from casting doubt on standpoints. - Burden of proof rule

A party that advances a standpoint is obliged to defend it if asked by the other party to do so. - Standpoint rule

A party’s attack on a standpoint must relate to the standpoint that has indeed been advanced by the other party. - Relevance rule

A party may defend a standpoint only by advancing argumentation relating to that standpoint. - Unexpressed premise rule

A party may not deny premise that he or she has left implicit or falsely present something as a premise that has been left unexpressed by the other party. - Starting point rule

A party may not falsely present a premise as an accepted starting point nor deny a premise representing an accepted starting point. - Argument scheme rule

A party may not regard a standpoint as conclusively defended if the defense does not take place by means of an appropriate argumentation scheme that is correctly applied. - Validity rule

A party may only use arguments in its argumentation that are logically valid or capable of being made logically valid by making explicit one or more unexpressed premises. - Closure rule

A failed defense of a standpoint must result in the party that put forward the standpoint retracting it and a conclusive defense of the standpoint must result in the other party retracting its doubt about the standpoint. - Usage rule

A party must not use formulations that are insufficiently clear or confusingly ambiguous and a party must interpret the other party’s formulations as carefully and accurately as possible. (Van Eemeren, Grootendorst & Snoeck Henkemans, 2002, pp.182-183—which I got from Wikipedia, meaning that argumentation textbooks are lagging behind Wikipedia)

- Freedom rule

These rules are anti-demagoguery rules. If people argued by these rules, demagoguery would not be a problem, and demagogues would be strange relatives in your twitter feed that you eventually block because they’re irritating.

But here is the important for teaching, and especially about “open” assignments: A person cannot assess the logic of an argument by these rules without knowing the conversation in which the author is engaged.

So, I’ll say again, unless the teacher really does read all the arguments about all the issues, a teacher cannot assess the logic of an argument.

What I hope I made clear is that fairness across groups is the antidote to demagoguery. Demagoguery says our group is good, our group is threatened with extinction, anything done for our group or by our group is good, and anyone not in our group should be silenced. When people deeply engaged in demagoguery are asked to behave in a world of fairness, they respond with violence (because they know they can’t win if they have to abide by the ten rules listed above).

And that means that teachers should assign topics about which we can model fairness. We should assign paper prompts about which we don’t have a right answer, that aren’t about identity, and on which we can fairly assess the logic.

I spend a lot of time wandering around dark corners of the internet, and I’m a historian of public deliberation, and I’m normally the one to say that this problem is not new, but even I believe that we are in an era in which the very notion of democracy is under attack.

And it all comes down to fairness.

Demagoguery dies when people promoting their in-group talking points have to argue within those ten rules. So, as teachers, we should live by and impose those rules. It isn’t easy, and it’s operating against our culture of demagoguery, but I think it’s the right, the compassionate, fair, inclusive, and rational thing to do. Just to be clear, what I’m saying is that, in a culture of demagoguery, people assess arguments this way:

There is one perspective from which the truth about our situation can be perceived, and it’s the perspective of TRUE [Americans, liberals, conservatives, lefties, environmentalists, squirrel-haters].

So, to determine if an argument is good, you first determine whether the person making the argument is a true [member of the in-group].

To counter that THOSE people aren’t really good isn’t undermining a culture of demagoguery; it’s reinforcing it.

We need to stop arguing about bias; we need to talk about democracy. And democracy is about fairness. It’s about doing unto others as we would have them do unto us. And that should be a value about which all of us can agree.