We are, again, at a point in time when the term “demagoguery” is getting thrown around, or, perhaps more accurately, the accusation. As has often happened, the prominence, and disturbing power of an individual, gets us to worry about that kind of rhetoric, but specifically as a question of identity. We are talking about whether this or that rhetor is a demagogue. The same thing happened with Joseph McCarthy, Adolf Hitler, Charles Coughlin, Huey Long, George Wallace—when those figures were in the news, demagoguery was a popular and popular scholarly topic.

But, as will be mentioned later, in rhetoric the term (and scholarly project) were abandoned in the 70s, largely because the project was subtly circular, insofar as definitions amounted to “an effective rhetor with whom I disagree.” I think scholars and teachers of rhetoric have a really important and useful place we can intervene here, but we need to work to define the term in ways that are more rigorous and self-reflective. For several years, I’ve been trying to revive scholarly interest in the project, and below I’ll explain what got me interested—but with a focus on demagoguery rather than demagogues—and now suddenly it’s hot again.

I’d like us not to make the same mistakes that were made in the past, as far as how we, as scholars, teachers, and critics, use the term and how we imagine demagoguery working. Demagoguery is not actually a timely issue; it’s a timeless one. Demagoguery isn’t about evil and magically powerful individuals who sucker the masses; it’s about what a culture considers normal methods of political participation.

My problem with many definitions of demagoguery is that they emphasize the identity and motives of the rhetor, and that emphasis comes from what I think is a methodological error. Scholars begin by compiling a list of prominent and powerful individuals they consider dangerous. They then look to that set of individuals to see what they have in common in order to define what is wrong with that rhetoric.

Nicolas Taleb describes what he sees as a methodological error in regard to popular and even scholarly claims about what makes a successful investor. He uses the analogy of a thousand people who play Russian roulette. A lot of people will survive that first shot; some number will make it to five shots. Imagine, he says, that pundits, journalists, and scholars then approached those survivors to ask about their strategies in order to recommend them to people who want to win at Russian roulette. You would get useless information.

But it would look useful. To know that information was useless, you would have to look at the people who lost, as well as the people who won, to see if there really are strategies—if there are differences among people who didn’t make it past the first round and those who made it to the end. I think we’re in the same situation with trying to think about demagoguery—it isn’t some unusual phenomenon that guarantees success. It works in some situations and not others, and we need to think about that.

There are six methodological problems to consider with the “infer from rhetors I hate” project:

-

- Looking for the commonalities among successful and hated rhetors assumes what is at stake—that it was something about their rhetoric or identity that enabled them to succeed, rather than there being a tremendous amount of luck. If we want to know what does enable that success, we need to look at unsuccessful demagoguery.

- That method doesn’t enable us to see demagoguery we like—by beginning with rhetors we hate, we exclude consideration of our attraction to potentially damaging rhetoric.

- It also prohibits empirical research on demagoguery. And here I’m advocating a kind of research I don’t do, but that I think is valuable. If we could come up with a fairly rigorous definition of demagoguery, then we could use strategies like corpus analysis in order to be more precise in our claims of causality and consequences.

- Oddly enough, the standard criteria—motive, emotionality, populism—don’t even capture the most famous demagogues, or they end up capturing all political figures, so those criteria are both over- and under-determining.

- These criteria are demophobic and elitist, as though rich and intellectual people never fall for demagoguery, and that just isn’t true.

- Finally, by focusing on identities as the problem—bad things happen because we have powerful individuals who are demagogues—we necessarily imply a policy solution of purification. If the presence of these bad people is the problem, then we should purify our community of them. Since I’ll argue that policies of purification are, in fact, one of the consistent characteristics of demagoguery, that would mean, in the scholarly project of criticizing demagogues, we’re engaged in demagoguery.

Here’s my argument: I think we can distinguish demagoguery from other forms of persuasive discourse on the basis of the presence of certain rhetorical moves, not the identity of the rhetors. I think, also, we should talk about the effectiveness of demagoguery in terms of how it plays into the informational worlds that people inhabit. Demagoguery isn’t an identity; it’s a relationship.

For the scholarly project of identifying demagoguery to be effective, we need to be working with a definition that enables us to see when we are drawn to it. In addition, we need a model of demagoguery that plausibly explains a few odd characteristics about it. I’ll mention a couple:

-

- It’s obvious to us that Hitler, for instance, was a demagogue. But, clearly, he couldn’t have appeared as such to his followers—they wouldn’t have listened. If you read people who defend Joseph McCarthy (and there are many), they will argue that he wasn’t a demagogue because there really were spies in government. They don’t care that he didn’t actually identify any of those spies, that he caused to be fired people who were not spies—their argument is that he had a claim that was true in the abstract, but it doesn’t matter to them that his specific claims were entirely wrong and very damaging, not just to individuals, but to American foreign policy, especially anticommunism. His standards of “communist” ensured we lost experts who might have actually helped us in Vietnam But his defenders assume that, because he was, in a fairly abstract way, “right,” he wasn’t a demagogue. Another defense of demagogues—or ways that people try to refute the accusation—is to say the person isn’t a demagogue because he or she is nice, or a good person. I’ll come back to both of those.

- We talk about demagogues as magicians with word wands, who command entire populations. And while it’s true that the famous ones are politically effective through their rhetoric——demagogues are never saying anything unique. Scholars and biographers note the extent to which they were saying things exactly like a lot of other media outlets and rhetors. They were effective because they were saying things that were familiar—so what impact did they have? There is a scholarly argument as to just how personally anti-Semitic Hitler really was (I’d say very, but not everyone agrees) but there is no doubt that his public rhetoric was in line with what various Catholic and Lutheran organizations and media were promoting, with dominant racialist theory (some of which was popular in the US), and with a variety of far-right volkisch groups.

As Ian Kershaw says,

“Time after time, Hitler set the barbaric tone, whether in hate-filled public speeches giving him a green light to discriminatory action against Jews and other ‘enemies of the state’, or in closed addresses to Nazi functionaries or military leaders where he laid down, for example, the brutal guidelines for the occupation of Poland and for ‘Operation Barbarossa’. But there was never any shortage of willing helpers, far from being confined to party activists, ready to ‘work towards the Fuhrer’ to put the mandate into operation” (Hitler, the Germans 43)

It’s also useful to remember that neither the Holocaust nor WWII could have happened had Hitler been the only rhetor promoting his anti-Semitism and visions of world conquest. He had a propaganda machine. And that propaganda machine existed before he came to power, before he even began making speeches in beerhalls—the Nazis didn’t write Protocols of the Elders of Zion.

Hitler and the Nazis radicalized existing beliefs about German purity and honor, and how the nation was threatened by immigrants, ethnic minorities, non-Christians, intellectuals, unions, homosexuals, leftists, and feminists. But those beliefs were preexisting.The assumption of a worldwide Jewish conspiracy that started World War I, ended it when Germany was about to win, and/or was busy seducing non-Jewish woman shows up as plot point in popular movies—not just German ones—and even popular spy thrillers in English by authors like John Buchan or Leslie Charteris.

Robert Gellately says,

“Nazi propaganda was not, and could not, be crudely forced on the German people. On the contrary, it was meant to appeal to them, and to match up with everyday German understandings [….] Thus, far from forcing unwanted or repellant messages down the throats of the population, Hitler and the Nazis carefully tailored what they said, wrote, and especially what they did, in order to win and hold the support of the people.” (Backing Hitler 259)

By the end of the war, which Germans supported, large numbers of Germans also supported the existence and use of the slave labor and death camps—things they would not have supported to the same extent before the war. The relationship between Hitler and the shift in German ideology isn’t simple to describe.

I’m not endorsing what is called the “functionalist” explanation of the Holocaust—the notion that Hitler as an individual didn’t matter, because the institutions were essentially driving themselves. I don’t think that’s the case—I think Kershaw has described it elegantly: it was the combination of Hitler’s personal fanaticism and charismatic leadership, a set of governmental arrangements and practices, conditions of the war, enthusiasm on the part of many people, and apathy on the part of others.

Just as scholars have struggled to define the exact relationship of Hitler’s personal beliefs and historical forces in the Holocaust, the field of rhetoric is struggling to find an accurate narrative for how rhetorical change happens. Narratives of persuasion toggle among fatalism, determinism, magical rhetoric, and the two modern dogma that Wayne Booth identified years ago, scientism and motivism.

I didn’t come to an interest in demagoguery via loathing individual rhetors. I came via Jurgen Habermas and Hannah Arendt through the American antebellum debate over slavery. Briefly, Habermas famously distinguished communicative versus strategic action, and most scholarship (and even pedagogy) following his line of thought was about additions to and critiques of his notion of communicative action—was it universalist, how does empirical research support it (or not). One criticism from feminist scholars such as Seyla Benhabib, I.M. Young, and Bonnie Honig, was that it was excessively averse to conflict, especially passionate conflict, and too restrictive in its formulation of reason.

Arendt’s argument for thinking (and especially her model of thinking as imagination) and her advocacy of agonism seemed a good corrective to what might be excessively rationalist about Habermas’ vision of deliberation, and also much more pragmatic. In terms of pedagogy, Tom Miller’s argument about the history of rhetorical pedagogy seemed to provide the keystone—we used to have a civic and agonistic model of teaching rhetoric, and then we shifted to an expressivist and hyper-individualized version of writing.

But here I ran up against a historical argument. If the best form of rhetorical pedagogy is civic-agonistic, and there are direct benefits to the quality of public deliberation from such a pedagogy—if the dream civic space is Habermasian/Arendtian— and such a pedagogy was dominant in the antebellum era, then why was the debate over slavery such a train wreck?

A graduate student asked me that in a seminar, and I didn’t have a good answer. So I ended up writing a book about the proslavery argument.

The argument for slavery was just a rhetorical trainwreck. Within the same document, sometimes on the same page, there would be an argument that appealed to premises that contradicted the premises of another argument—slaves are happy, slaves are always just seconds from race war, slavery will die out, slavery is eternal.

There were ways in which proslavery ideology was consistent—it was consistently authoritarian, for instance, and consistently resistant to policy deliberation or pragmatic argumentation. But, it was logically inconsistent, in terms of major premises contradicting one another, and even sometimes claims in perfect opposition. It also increasingly came to seem it wasn’t about the claims qua veridical or assertoric claims—they were phatic. What mattered about them was the extent to which they were performances of ingroup loyalty. Thus, consistently, what should have been policy deliberations—what are the long-term chances of maintaining slavery, what should happen with tariffs, what and whether railroads should be built, what should be done about the exhaustion of the soil, should we have Sunday mails, should we secede—were not times when people considered multiple alternatives, the feasibility and solvency of various plans, but were taken exclusively as opportunities for rhetors to engage in an ingroup loyalty oneupsmanship regarding their commitment to slavery.

In such a world, rational approaches to argumentation were framed as dithering cowardice, and the best way to show loyalty was to advocate a risky—even implausible—course of action. This is what I ended up calling “the rhetorical power of the irrational rhetor.” After all, supporting a reasonable plan doesn’t show ingroup loyalty as much as advocating an openly unreasonable one—that’s what shows you are a true believer, and that you believe you have God on your side. To advocate rational and inclusive deliberation was characterized as dangerously disloyal, perhaps even the consequence of such an advocate being the knowing or unknowing tool of evil forces. Dissent of any kind, even dissent about the feasibility of proposed courses of action—even if a rhetor explicitly agreed with the goals, agreed with the need, and was simply trying to debate strategy–was “refuted” with identity arguments—that you were a bad person for doubting the ability of the ingroup to succeed. And you were a bad person because you weren’t sufficiently concerned about the need.

In other words, rhetors responded to criticism of the plan with reassertion of the desperate need and performances of ingroup loyalties.

It’s important to remember that, despite the way we talk about the slavery debate, there were not two sides. Off the top of my head I generated fourteen. I’m not sure it’s useful to think of them as “sides,” as much as sets in a Venn diagram, and those positions morphed, split, and combined in the thirty years that slave states were threatening secession over the issue. A few of them include:

-

- proslavery (slavery as an active good);

- proslavery (necessary evil);

- proslavery (slaveholders should be able to maintain slaveholding even if living in non-slave states);

- proslavery (it will die out on its own so we don’t need to do anything);

- proslavery pro-secession (knowing it would provoke a war);

- proslavery anti-secession (Unionists, who believed the Union could be made even more favorable to the slaveholder political agenda, and secession was unnecessary);

- proslavery promanumission (slaveholders should be able to free their slaves if they choose, generally associated with also believing that slaveholders should be allowed to teach their slaves to read);

- proslavery antimanumission (the state should be able to micromanage slaveholders, such as prohibiting the teaching of reading, prohibiting manumission, and so on).

- NIMBY antislavery (restrict it to the existing slave states);

- anti-proslavery (the Slave Power is restricting the rights of all to protect slavery—right to petition, free speech, freedom of religion, states’ rights);

- anti-antislavery (abolitionists are making things worse by provoking slaveholders and proslavery politicians);

- pro-colonization anti-slavery (slaves should be freed without governmental coercion and sent “back” to Africa);

- antislavery gradual abolition (slave states should follow the same procedures as had been used in New York and Pennsylvania, some of the people advocating this argued that slaveholders be recompensed for their losses);

- immediate emancipation and full citizenship.

The list could go on, but I think the point is made. Proslavery rhetors didn’t want to acknowledge the broad range of possible stances, since it undermined their alarmist rhetoric—that if you weren’t in favor of the most extreme policies, then you were an abolitionist (or one of their stooges) advocating slave rebellion and race war.

At the time I was working on that book, the buildup to the Iraq invasion was happening, and I was watching the same thing happen—the demonization of deliberation (by which I mean that deliberation was actually characterized as serving the devil), dissent was treated as treason, and the complicated array of positions regarding the invasion were restricted in the most powerful media to two: for the Bush plan or against doing anything about terrorism. (In some corners, there was either oppose any military action or threat in regard to Iraq or support a war for oil.)

In fact, if you were paying attention, you could create a description of the various often overlapping positions as complicated as the one regarding slavery:

-

- in favor of immediate invasion;

- in favor of threatening immediate invasion until Saddam Hussein complied with the UN;

- in favor of invasion after success in Afghanistan;

- in favor of UN-supported invasion, or an invasion with a coalition of Middle Eastern countries (like the Persian Gulf War);

- in favor of invasion with what the Pentagon considers adequate forces;

- opposed to invasion unless Saddam stops cooperating with the UN inspectors (this position emerged after he started cooperating);

- opposed to invading Iraq, but in favor of the Afghanistan efforts;

- opposed to any troops on the ground, but in favor of bombing;

- opposed to any invasion of any kind.

Again, we could come up with a longer list—that isn’t my point. The point is simply that it wasn’t a pro- or anti-invasion, but the public discourse kept reducing the complicated situation to “us” and “them.”

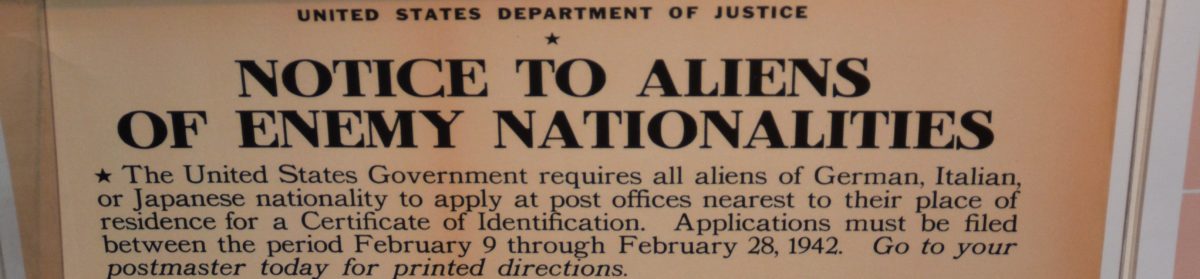

And various other historical train wrecks had a similar pattern—Japanese internment, the Holocaust, the Sicilian Debate, the Mytilinean Debate, segregation, American anti-immigration rhetoric, LBJ policy in regard to Vietnam…the complicated political situations were bifurcated into two groups, and, instead of arguing policy, people argued which of the two groups was better, as though that would settle what policy we should follow. And that’s when I got interested in demagoguery.

I’ve told this long story of my scholarly and teaching wanderings for two reasons. First, I didn’t come to demagoguery via demagogues, but via disastrous community decisions—slavery, segregation, Japanese internment, escalation in Vietnam, the Sicilian Expedition, the Holocaust. In fact, in most of these cases, there wasn’t a demagogue, but there was demagoguery. Second, because of that orientation, the question became what rhetorical practices were normalized in these discourse communities?

Once you stop looking for demagogues, and instead look at times that communities scapegoated some group to the point of state-legitimated violence, then you can see a similar set of characteristics:

-

- Policy questions are reduced to questions of identity, which are bifurcated (with us or against us), and motive (good or bad);

- Nuance, uncertainty, deliberation, and skepticism are rejected as unmanly and disloyal (except for skepticism about claims made against ingroup members);

- The community is reduced to the ingroup (so that, even if “they” are legally or historically part of the community, they are never considered “real” members);

- An outgroup is scapegoated for all the ingroup’s problems;

- Public discourse is predominantly performance of ingroup loyalty;

- The community is described as threatened by the mere presence, let alone political power, of that outgroup, and so the solution is some version of purifying us of them;

- Ingroup loyalty is demonstrated by insisting that policy discussions are unnecessary because the correct course of action is obvious to all people of goodwill (disagreement is fake—either the person disagreeing doesn’t really disagree, or is fooled by the outgroup);

- The discourse is heavily fallacious, but not necessarily emotional, and can involve appeals to authority and expertise, and can look as though there is a lot of “evidence;”

- Public discourse focusses almost exclusively on the “ill” or need portion of an argument, with the major ill being an existential threat to the ingroup—because we are threatened with extinction, concerns like due process, human rights, and fairness are luxuries we can’t afford;

- Finally, while there are overlaps with fascism (especially as Robert Paxton describes it), it isn’t necessarily fascist, or even political.

This is what I would suggest should serve as the criteria we look at, but I think this is a question open to empirical testing. Instead of looking at rhetors we hate, though, we would look at times of extermination, expulsion, or group oppression.

This list isn’t entirely new, and it isn’t as though no one else has ever remarked on these characteristics—Walter Benjamin and Giorgio Agamben have both noted the state of exception, Arendt remarked on the lack of perspective-shifting in someone like Adolph Eichmann, and I’ve obviously been influenced by Kenneth Burke’s 1939 piece on Hitler’s rhetoric, George Lakoff’s work on Strict Father Morality, political scientists’ work on authoritarianism and “stealth democracy,” and Chip Berlet and Mathew Lyon’s work on Right Wing Authoritarianism. I’ve tried to focus, as I say, not just on famous rhetors like Hitler, nor only on right-wring demagoguery, in fact, not even strictly on political demagoguery. That accounts for some of the differences.

These practices don’t always lead to the expulsion or extermination of some group, for several reasons. First, demagoguery is powerful depending on the extent to which that kind of scapegoating and fear-mongering is perceived as normal. In my classes, I often use examples from PETA—I’m a vegetarian and animal lover opposed to most animal experimentation. I use PETA because I’m sympathetic to their ends, such as an article about trying to reduce interstate and international trade in various constricting snake species; the article ends up scapegoating snake owners generally, and owners of venomous snakes especially. It’s demagoguery, but probably with little impact—demagoguery about pitbulls, on the other hand, has had considerable impact.

In addition, Michael Mann’s work on ladders of extremism suggest why demagoguery can stop. His argument is that, at any given moment, the conflict between two groups could get resolved by the community as a whole choosing to revert to what he calls “normal politics.”

He mentions that heightened exterminationist rhetoric can be motivated by an ambitious rhetor who thinks it’s useful as a mobilizing passion. If the rhetor gets what he (usually) wants, then he might abandon the rhetoric (as Ward seems to suggest was the case with many southern politicians, who used race-baiting only when it would help them win an election). It can also get “resolved” by the ougroup voluntarily leaving or settling for oppression.

I’ll note that if, however, the demagoguery is motivated by a desire for political power, or increased viewers, or a plan to distract people from some other situation, then the outgroup that leaves will simply be rhetorically replaced by another outgroup to scapegoat. Now that it’s difficult to rouse much political power by appealing to fears about Irish and Italians, one sees exactly the same anti-immigration rhetoric applied to “Mexicans” and “Muslims.” Fox News had considerable coverage of Ebola prior to the 2014 election, connected to fears about immigrants—once the election was over, that coverage dropped.

At the beginning I said that I think we need to think about demagoguery as a relationship. Here I’m saying that part of the relationship is to other information available to the consumer. Demagoguery only works when we don’t think it is demagoguery, and we don’t think it is when we have a bad definition—one that relies on inference of motive, unhelpful assumptions about how easy it is to see if something is false, and equally unhelpful assumptions about what it means for an argument to be “rational.” I don’t have a lot of time to explain them, so I’m going to go through them quickly. Basically, my argument is that demagoguery works because our lay notions of what it means to participate effectively in public discourse encourage us to have unhelpful criteria for “bad” kinds of rhetors.

Here are some assumptions that people make about political decisions:

-

- When it comes down to it, the solutions to our political problems are straightforward. Our political issues are the consequence of not having enough good people in office—instead, we have professional politicians who aren’t really trying to solve things. (Stealth Democracy)

- Good people do good things, it’s easy to recognize when someone is a good person, or when a plan of action is good. So, we don’t need to argue about policy—we just need to vote for the good people who are above (our outside of) professional politics.

- Good people speak the truth, and they don’t try to alter it through rhetoric—they are transparent. Thus, you should trust people who strike you as unfiltered, and who say things that resonate with you immediately.

- A “rational” argument is a claim that is true (and that you can recognize easily to be true) supported by evidence, and presented in an unemotional way.

I’ve been very moved by Ariel Kruglanski’s work on what he calls “lay epistemologies,” perhaps because he confirms what Aristotle says. Kruglanski says that people reason syllogistically—this person is a Canadian; Canadians are polite; therefore, this person must be polite.

Our popular culture and, unhappily, our textbooks in rhetoric and composition, remain dominated by the rational/irrational split, despite that being a relatively recent development, and it not being what research in cognitive psychology shows. What the research shows is that there is not some distinction between emotions and logic, but a division between System 1 and 2 thinking: between cognitive shortcuts and metacognitive processes.

In System 1, you simply decide whether new information fits with what you already know. In System 2, you think about whether how you know is a good process. We spend most of our time in System 1, as we should, but we should make political decisions using System 2. Demagoguery says we don’t need to do that.

Demagoguery works with all of us when we believe that all we need is System 1—the demagoguery that “moves” us is the one that resolves our cognitive dissonances by persuading us that what we have always already known is absolutely true. We aren’t moved by new information, but by a new commitment to old beliefs.

Demagoguery depoliticizes politics, in that it says we don’t have to argue policies, and can just rouse ourselves to new levels of commitment to the “us” and purify our community or nation of them. It says that we are in such a desperate situation that we can no longer afford them the same treatment we want for us.

Metacognition is demagoguery’s worst enemy, and there is a simple way to move to metacognition—would I think this was a good argument if it were made in service of the outgroup political agenda. If people thought that way, then demagoguery would be restricted to moments of hilarity on youtube about music you hate.

In other words, I just spent 45 minutes telling y’all that what most prevents demagoguery is a culture in which we believe that you should “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” And that’s what we should teach.

Thank you again, Trish. I’m gonna direct my students’ attention to this post.