What I want to do today is begin by talking a little bit about the place of “demagoguery” in contemporary rhetorical scholarship, then offer my own definition, and then show its application in regard to someone I admire. And, in a way, that’s the whole project in a nutshell: scholarship in rhetoric can’t serve a useful critical purpose if it just comes down to scholars praising people we like and blaming people we don’t—rhetorical scholarship should be deliberative, and neither epideictic nor judicial.

Jurgen Habermas’ “What is universal pragmatics” has a wonderful footnote with a diagram of kinds of discourse–communicative versus strategic action.

As is common among scholars of public discourse, Habermas’ focus is on communicative action, and the rest of his career has been spent trying to identify the ontological bases, precise criteria, and most promising models for public deliberation as opposed to instrumental reason, a.k.a., strategic action. As I said, that’s fairly common for scholars of public discourse, who tend to focus on what deliberative discourse is, how to teach it, how to foster it, how to balance inclusion and civility. Since I spent a chunk of my career working on that problem, I’m not critical of that kind of scholarship—it’s important.

But we have tended to ignore the other side of the chart– why are people so drawn to instrumental reason even in cases where deliberative approaches would be more helpful? It isn’t particularly controversial in business, management, counseling, mediation, interpersonal mediation, and a variety of other fields that businesses, communities, and relationships benefit more from approaches to decision-making that are toward the deliberative rather than toward the strategic action side.

And by “toward deliberative side” I don’t mean anything particularly high-minded or complicated – in fact, I have fairly low standards about what constitutes deliberative discourse. I’m not necessarily talking about a community in which people are nice to each other, or unemotional, or in which no one is offended, or everyone feels safe — I just mean one in which it’s considered necessary to listen to, and therefore fairly represent, the other side.

The notion that you should listen to your opposition seems to me to be a no-brainer–you can’t even be sure that you actually disagree unless you’ve listened enough to know what your interlocutor is arguing. And, if you and that person aren’t just vehemently agreeing, and you want to change the mind of the person with whom you’re disagreeing, it’s going to be very hard to persuade them to change their mind unless they feel you’re engaging the arguments they’re really making. Yet early on in my teaching I discovered that a fair number of my students thought it was actively dangerous to listen to the opposition, let alone restate their argument in a way the opposition would consider fair.

So I became interested in how to try to persuade people to listen to the opposition, and that task necessarily led me to think about two questions: first, what makes listening to the opposition dangerous; second, what makes living in a world of demonizing, dehumanizing, and irrationalizing the opposition attractive, even pleasurable.

Once you’ve posed that second question you may well find yourself, as I have, studying what I’ve ended up thinking of as train wrecks in public deliberation– times that communities took a lot of time and a lot of talk to come to a decision they later regretted, and concerning which they had all the evidence they needed in the moment to come to different conclusions.

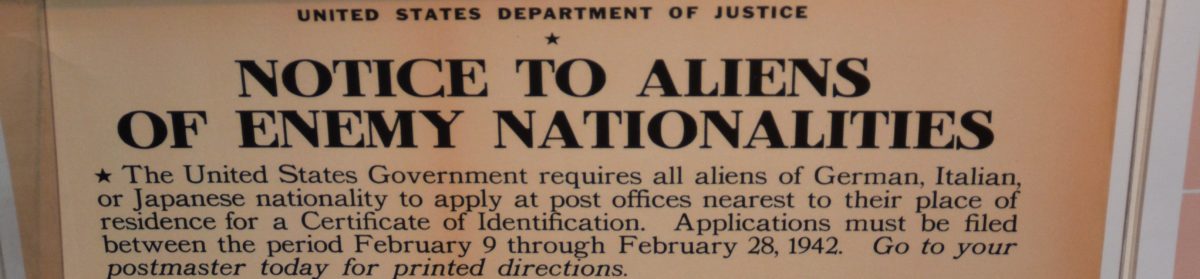

Thus, I’m not talking about times when communities had no choice, or inadequate information, or when they made decisions I think they shouldn’t have made. I mean things like the Sicilian expedition of 415 BCE, the Salem witch trials, the US commitment to slavery and then segregation, anti-immigration fear mongering of the 1920s and the related forced sterilization of around 65,000 people in the United States, the Holocaust, Japanese internment, LBJ’s decision to escalate in Vietnam, the Iraq invasion, and other more specific incidents, such as Hitler’s refusal to order a retreat from Stalingrad or Haig’s insistence on the direct approach in various World War I battles.

And there are a few common characteristics about these incidents, in terms of what had become “normal” political discourse—specifically, heightened factionalism, so that politics became a performance of ingroup loyalty, and the ethos of the nation was reduced to one faction—that is, pluralism is demonized–and thwarting the opposition is just as much a laudable goal as enacting policies, because there is no sense that multiple factions might be legitimate or that the community benefits from disagreement. The nation is the party, and failure to support the party is treason. Obviously, in such a world, compromise and bargaining, let alone inclusive and pluralist deliberation, are disloyal, cowardly, and evil.

So it began to look to me as though there was a strong correlation between bad decisions and bad decision-making processes — not that they are necessarily and inevitably related, but that they often are, and so I started trying to identify the specific characteristics of those bad decision-making processes.

Largely because I don’t like neologisms, I started using the term demagoguery for that approach to public discourse. That may have been a mistake. Often people engaged in this kind of work do come up with a new term. Chip Berlet and Matthew Lyon use the term right-wing populism; David Neiwert calls it eliminationist; Kenneth Burke describes the same phenomenon in regard to Hitler, doesn’t use any term in particular. That’s something worth discussing—whether I should simply use a different term, rather than try to salvage a deeply troubled one.

Early in this project I, like most other scholars of this kind of rhetoric, focused on individual rhetors, on demagogues; I’m now certain that was a mistake.

Scholarship on demagogues went out of fashion in rhetoric in the seventies, largely because that scholarship consistently appealed to premises that were rationalist, elitist, and anti-democratic. Most definitions of “demagogues” emphasized the emotionalism of their arguments, the populism of their policies, and the selfishness of their motives. The conventional criticism of such scholarship was four-part:

-

- The criticism looked rhetorical, but it was really political—”demagogue” was simply a term for an effective rhetor in service of a political agenda that the scholar didn’t like;

- By condemning demagogues for emotionalism, scholars were idealizing a public sphere of technocratic and instrumental argument, and necessarily banishing individuals and groups who were passionate about their cause—since victims of injustice tend to feel pretty strongly about their situation, prohibiting demagogues would have a disproportionate impact on marginalized and oppressed groups;

- Demagogues are always “men of the people,” so the scholarship on demagogues is anti-populist—why assume that only the masses are misled?

- Scholarship condemning demagogues is demophobic—the (false) assumption is often that the rise of a demagogue is the consequence of “too much democracy,” once again implying that the elite don’t make mistakes.

I agree with all of those criticisms—I do think that much existing scholarship on demagogues is not particularly helpful for doing much other than saying, “I don’t like that rhetor.” But I don’t think that makes the project hopeless—I think the problem comes from focusing on demagogues, rather than demagoguery.

Take, for instance, Kenneth Burke’s 1939 brilliant analysis of Hitler’s Mein Kampf, and the odd logical problem it falls into by trying to explain Nazism through Hitler’s individual psychology. According to Burke, Hitler became obsessed with the Jews because he lost arguments to them in Vienna (to be honest, I think that might have been a factor, but his own anxiety that he might be Jewish was probably more important), but, if that’s what made him anti-Semitic, why did his anti-Semitic rhetoric work? Did every member of his audience go to Vienna and lose an argument to a Jew? Of course not. Whatever Hitler’s personal motivations were—he was anxious about his heredity, he was out-argued by Jews–, they don’t explain why he was effective with people who didn’t have those anxieties or experiences.

Burke set out to analyze Hitler’s rhetoric because of Hitler’s political power—the scholarly method was to select the rhetor and then look a the rhetoric. Similarly, scholars of demagogues, ranging from James Fennimore Cooper to Michael Signer, generally use the process of beginning with political figures they considered demagogues, and then looking to see what those figures had in common.

That method guarantees that what they will have in common is that the scholar doesn’t like them. The “demagogues” are always in the scholars’ outgroup, and that may be why there is so much motivism. Scholarship on demagogues generally focuses on the motives of the demagogue—demagogues, unlilke statesmen (thank Plutarch for that fallacious distinction), look out for themselves. They want power, but statesmen (and I use the gendered term deliberately) want what’s best for the country or community.

Since people attribute bad motives to members of the outgroup and good motives to members of the ingroup for exactly the same behavior—an ingroup member who makes a lot of money is a hard worker, and an outgroup member who makes a lot of money is greedy–, this criterion of motive means that it will never help us identify ingroup demagogues. After all, the basic premise of this approach to finding demagogues is that they are bad people—if we admire someone, we won’t admit they’re bad, so they can’t be demagogues.

In addition to the problem that it prevents us from seeing when we’re being persuaded by demagoguery, this criterion doesn’t even capture the most notorious demagogues, who almost certainly sincerely believed that they were doing the right thing for their communities and countries. Hitler thought the Holocaust was necessary and justified and right. He meant well.

So focusing on identity and “bad motives” doesn’t help us identify the kind of rhetoric we want to.

The emphasis on demagogues presumes that, as Burke said of Hitler, they can lead a great country in their wake—they are masters in control of the masses. But, if you look at the leadup to the train wrecks, that isn’t what you see at all. You don’t see an individual who magically changed what the masses thought—Hitler would never have succeeded without considerable help from the elite, and, famously, Hitler wasn’t saying anything new. People moved to support Nazism weren’t all moved by Hitler (Adolf Eichmann doesn’t mention Hitler’s rhetoric), and Hitler’s rhetoric wouldn’t have been effective if it had been entirely new. It was commonplace.

Demagogues don’t create a wake—they ride a wave.

Probably more important, if you go about it by looking at the leadup to train wrecks, you sometimes don’t see a demagogue at all, but you do see demagoguery. Proslavery forces didn’t have a single rhetor who led everyone along—the antiabolitionist alarmism, scapegoating, and general demagoguery wasn’t emanating from one rhetor, but was almost ubiquitous. It was in newspapers—even of opposing parties—speeches in Congress on all sorts of topics (including the question of the Sunday mails), novels, poetry, plays; it was used by major figures, minor figures. Prosegregation rhetoric was similarly demagogic, ubiquitous, and headless—there wasn’t a figure from whom it emanated. There wasn’t an individual who led the US in his wake; there were a lot of figures who decided to ride a wave.

If we look at decision-making processes rather than demagogues, I think we’d end up with a definition like this:

Demagoguery is a discourse that promises stability, certainty, and escape from the responsibilities of rhetoric through framing public policy in terms of the degree to which and means by which (not whether) the outgroup should be punished for the current problems of the ingroup. Public debate largely concerns three stases: group identity (who is in the ingroup, what signifies outgroup membership, and how loyal rhetors are to the ingroup); need (usually framed in terms of how evil the outgroup is); what level of punishment to enact against the outgroup (restriction of rights to extermination).

There are certain recurrent characteristics. It

-

- reduces all policy discussions to questions of identity and motive, so there is never any need to argue policies qua policies;

- polarizes a complicated political situation into us (good) and them (some of whom are deliberately evil and the rest of whom are dupes);

- insists that the Truth is easy to perceive and convey, so that complexity, nuance, uncertainty, and deliberation are cowardice, dithering, or deliberate moves to prevent action (naïve realism);

- is heavily fallacious, relying particularly on straw man, projection, appeal to inconsistent premises, and argument from conviction;

- is not necessarily emotional or vehement, but there is considerable emphasis on the “need” portion of policy argumentation (which is generally an “ill” caused by the presence or actions of “them”) often with implicit or explicit threats that “we” (the ingroup) are faced with extermination, emasculation, and/or rape;

- draws on certain “motivational passions” (in Robert Paxton’s terms) shared with fascism, although it can be used in favor of non-fascist political agenda, and even in non-political circumstances.

One of the advantages of this approach—demagoguery rather than demagogues, or rhetoric rather than identity—is that it can enable us to see ingroup demagoguery.

For instance, take two people who a personal hero of mine: Earl Warren.

In the spring of 1942, California Attorney General Earl Warren testified before the Tolan Commission regarding the mass imprisonment of Japanese Americans. A typical passage of his testimony concerns a map he gave the Committee showing Japanese land ownership. He explains what the map shows:

Notwithstanding the fact that the county maps showing the location of Japanese lands have omitted most coastal defenses and war industries, still it is plain from them that in our coastal counties, from Point Reyes south, virtually every feasible landing beach, air field, railroad, highway, powerhouse, power line, gas storage tank, gas pipe line, oil field, water reservoir or pumping plant, water conduit, telephone transmission line, radio station, and other points of strategic importance have several — and usually a considerable number — of Japanese in their immediate vicinity. The same situation prevails in all of the interior counties that have any considerable Japanese population.

I do not mean to suggest that it should be thought that all of these Japanese who are adjacent to strategic points are knowing parties to some vast conspiracy to destroy our State by sudden and mass sabotage. Undoubtedly, the presence of many of these persons in their present locations is mere coincidence, but it would seem equally beyond doubt that the presence of others is not coincidence. It would seem difficult, for example, to explain the situation in Santa Barbara County by coincidence alone. (National defense migration. Hearings before the Select Committee Investigating National Defense Migration, House of Representatives, Seventy-seventh Congress, first[-second] session, pursuant to H. Res. 113, a resolution to inquire further into the interstate migration of citizens, emphasizing the present and potential consequences of the migration caused by the national defense program. pt. 11; 10974)

Notice that this argument, in favor of mass race-based imprisonment without trial, is neither emotional nor populist. And Warren was not motivated by political or personal gain—he sincerely believed that he was doing the right thing. He doesn’t fit common, or even many scholarly, definitions of a demagogue.

And, too, notice all the hedging—”Notwithstanding” and “It would seem difficult.” And notice his adopting the posture of a reasonable person—he isn’t saying all Japanese are knowingly part of the conspiracy. He isn’t unreasonable; he acknowledges some coincidence. So, his assertion that this can’t be coincidence seems more reasonable because of his having established himself as a person not prone to conspiracy theories.

In this passage, as throughout his testimony, there is a rhetoric of realism, factity, and submission to the data. Warren’s motives were good, in that he sincerely believed California was in danger—he didn’t gain any political power from taking this stance. It isn’t very emotional—as I said, there’s a matter of fact tone, with really only one brief exhortation—and it isn’t populist. He doesn’t fit the common definitions of demagogue.

But it is sheer demagoguery.

Warren is redirecting the complicated policy question—what, if anything, should we do about enemy nationals—into an identity question about “the Japanese.” Even the need question (should we fear sabotage) is reframed as an identity question: the Japanese can’t be trusted. His evidence, such as the maps, assume what’s at stake—it’s a circular argument.

The question he’s answering is whether the Japanese are trustworthy, and he’s answering that question with an enthymeme that has the major premise that the “the Japanese” are nefarious: The Japanese are nefarious because they own land near important war resources. This isn’t an argument he makes about Germans, Austrians, Italians, or French—he didn’t even bother to look into their land-owning patterns. And, of course, there are much more obvious and innocent explanations for those land owning practices—areas with a “considerable” Japanese population would have people engaged in fishing, farming, canning, and other activities that would make owning land near beaches, water, and power quite desirable.

Warren’s argument is unanswerable because it’s unfalsifiable.

But, Warren wasn’t a magician with a word-wand who swept citizens of the western states into a panic. There isn’t really even any good evidence that his testimony was widely reported—it probably had little impact on the juggernaut of mass imprisonment. It probably legitimated the racist panic of other people listening to him, by making them feel that their perceptions were reasonable and fact-based, but I doubt it changed anyone. He was appealing to perceptions about “the Japanese” that had been promoted by thousands of rhetors in the previous forty years—especially the Hearst papers, but also the Japanese Exclusion League, the FBI, the Los Angeles Times, major and minor politicians, and scholars of race. He was repeating what “everyone” knew.

Warren was refuted during the hearings—an expert on Norway pointed out that the notion of sabotage having had any impact on Nazi success was a myth, others noted that there hadn’t been sabotage at Pearl Harbor, and one person said about Warren’s argument that the lack of sabotage was proof that sabotage was planned, “I don’t think that’s real logic.” But he didn’t stick around to listen.

Warren later regretted his involvement in the mass imprisonment. He said, “Whenever I thought of the innocent little children who were torn from home, school friends, and congenial surroundings, I was conscious-stricken” (The Memoirs 149). But why didn’t he think of that in the first place? Because he didn’t imagine what his plan would really look like. He imagined the need—he had a great imagination when it came to the horrors of Japanese sabotage—but he didn’t imagine what his plan would actually look like.

Nor did he listen enough. He listened to police officers, sheriffs, and other law enforcement, but he didn’t listen to any of the people who testified against imprisonment. He didn’t listen to the opposition.

Warren was a good man, a progressive who helped clean up California politics, a compassionate man, whose leadership of the US Supreme Court gave us Brown v. Board, but a man drinking deep from demagoguery.

It isn’t clear that his demagoguery had much impact—the juggernaut was already started, and the really important demagoguery was all the anti-Japanese fear-mongering of various California media (especially the Hearst papers), organizations like the very powerful Japanese Exclusion League, even thrillers and their conventional representation of Japanese. Had Warren been the only one making the kind of argument he did, it wouldn’t have matter. He didn’t matter—his demagoguery did.

And that raises a point that is important. Demagoguery isn’t necessarily harmful. I mentioned it’s not always political—there is demagoguery in movie or music criticism that is actually pretty hilarious. As long as it’s a small amount, it’s fine. I generally say it’s like eating chocolate-covered caramels or sitting on the couch watching a bad movie. If that’s all you ate, or all you did, you’d get sick, but it isn’t always harmful.

So our problem now isn’t whether this or that political figure is a demagogue—that is itself accepting the major premise of demagoguery: that we can and should decide all political questions in terms of identity. We shouldn’t, as scholars, teachers, or citizens, be worrying about who is or is not a demagogue: we should be worrying about whether we are encouraging, rewarding, and deciding on the basis of demagoguery.

![]()

![]()