I’ve been asked why demagoguery rises and falls, more than once by people who like the “disruption” theory—that demagoguery is the consequence of major social disruption. The short version is that events create a set and severity of crises that “normal” politics and “normal” political discourse seem completely incapable of ameliorating, let alone solving. People feel themselves to be in a “state of exception” when things they would normally condemn seem attractive—anti-democratic practices, purifying of a community through ethnic/political cleansing, authoritarianism, open violation of constitutional protections.

When I first started working on demagoguery, I assumed that was the case. It makes sense, after all. And, certainly, in the instances that most easily come to mind when we think about demagoguery, there was major social disruption. Hitler rose to power in the midst of major social disruption: humiliation (the Great War and subsequent Versailles Treaty), economic instability (including intermittent hyperinflation), mass immigration from Central and Eastern Europe, an unstable government system.

And you can look at other famous instances of demagoguery and see social disruption: McCarthyism and the Cold War (specifically the loss of China), Charles Coughlin and the Great Depression, Athenian demagogues like Cleon and the Peloponnesian War, Jacobins and failed harvests. But, the more I looked at various cases, the weirder it got.

Take, for instance, McCarthyism and China. There are two questions never answered by people who blame(d) “the Democrats” for “losing” China is: what plan would have worked to prevent that victory? Did Republicans advocate that plan (so, would they have enacted it if in power)? McCarthy’s incoherent narrative was that spies in the State Department were [waves hands vaguely] somehow responsible for the loss of China. Were losing China a major social disruption, then it would have until that moment been seen as an important power by the people who framed its “loss” as a major international threat—American Republicans. But, prior to Mao’s 1949 victory in China, American Republicans were not particularly interested in China. In fact, FDR had to maneuver around various neutrality laws passed by Republicans in order to provide support for Chiang Kai Shek at all. After WWII, Republicans were still not very interested in intervening in China—they weren’t interested in China till Mao’s victory. So, why did it suddenly become a major disruption?

One possibility is that Mao’s victory afforded the rhetorical opportunity of having a stick with which to beat the tremendously successful Democrats (that’s Halberstam’s argument). If Halberstam is right, then demagoguery about China, communism, and communist spies was the cause, not the consequence, of social disruption. Another equally plausible possibility is that China becoming communist, and an ally of the USSR, took on much more significance in light of Soviet acquisition of nuclear weapons. So, the disruption led to demagoguery.

In other words, McCarthyism turned out not to be quite as clean a case as I initially assumed, although far from a counter-example.

Another problematic case was post-WWI demagoguery about segregation. In many ways, that demagoguery was simply a continuation of antebellum pro-slavery demagoguery, with added bits from whatever new “scientific” or philosophical movement might seem useful (e.g., eugenics, anti-communism). It wasn’t always at the same level, but tended to wax and wane. I couldn’t seem to correlate the waxing and waning to any economic, political, or social event, or even kind of event. What it seemed like was that it correlated more to specific political figures deciding to amp up the demagoguery for short-term gain (see especially Chapter Three).

Similarly, ante-bellum pro-slavery demagoguery didn’t consistently correlate to major disruptions; if anything, it often seemed to create them, or create a reframing of conflicts (such as with indigenous peoples). But, the main problem with the disruption narrative of causality is that I couldn’t control the variables—it’s extremely difficult to find a period of time when there wasn’t something going on that can be accurately described as a major disruption. Even if we look only at financial crises considered major (there was a major downturn in the economy that lasted for years), there were eight in the US in the 19th century: 1819, 1837, 1839, 1857, 1873, 1884, 1893, and 1896. Since several of these crises lasted for years, as much as half of the 19th century was spent in a major financial crisis.

And then there are other major disruptions. There were riots or uprisings related to slavery and race in almost every year of the 19th century. The Great Hunger in Ireland (1845-1852) and later recurrence (1879), 1848 revolutions in Western Europe, and various other events led to mass migrations of people whose ethnicity or religion was unwelcome enough to create major conflicts. And this is all just the 19th century only in the US.

Were demagoguery caused by crises, then it would always be full-throated, since there are always major crises of some kind. But it waxes and wanes, often to varying degrees in various regions, or among various groups, sometimes without the material conditions changing. Pro-slavery demagoguery varied in terms of themes, severity, popularity, but not in any way that I could determine correlated to the economic viability or political security of the system.

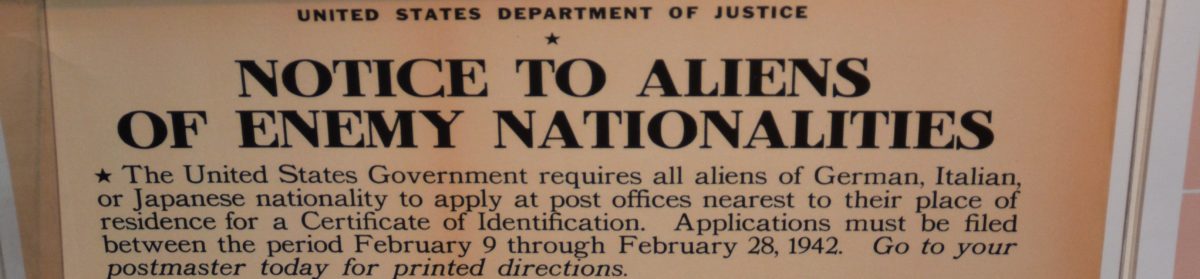

Anti-Japanese demagoguery was constant on the West Coast of the US from the late 19th century through at least the mass imprisonment in the 40s, but not as consequential or extreme elsewhere. One might be tempted to explain that discrepancy by population density, but there was not mass imprisonment in Hawaii, which had a large population of Japanese Americans. Anti-Judaism has never particularly correlated to the size (or even existence) of a local Jewish population; it’s not uncommonly the most extreme in situations almost entirely absent of Jews. And sometimes it’s impossible to separate the crisis from the demagoguery—as in the cases of demagoguery about fabricated threats, such as Satanic panics, stranger danger demagoguery, wild and entirely fabricated reports of massive abolitionist conspiracies, intermittent panics about Halloween candy.

I’ve come to think it has to do with two other factors: strategic threat inflation on the part of rhetors with a sufficiently large megaphone, and informational enclaves (and these two factors are mutually reinforcing). I’ve argued elsewhere that the sudden uptick in anti-abolitionist was fueled by Presidential aspirations; Truman strategically engaged in threat inflation regarding Soviet intentions in his speech “The Truman Doctrine;” the FBI has repeatedly exaggerated various threats in order to get resources; General DeWitt fabricated evidence to support race-based imprisonment of Japanese Americans. These rhetors weren’t entirely cynical; I think they felt sincerely justified in their threat inflation, but they knew that they were exaggerating.

And threat inflation only turns into demagoguery when it’s picked up by important rhetors. Japanese Americans were not imprisoned in Hawaii, perhaps because DeWitt didn’t have as much power there, and there wasn’t a rhetor as important as California Attorney General Earl Warren supporting it.

In 1835, there was a panic about the AAS “flooding” the South with anti-slavery pamphlets that advocated sedition. They didn’t flood the South; they sent the pamphlets, which didn’t advocate sedition, to Charleston, where they were burned. But, the myth of a flooded South was promoted by people so powerful that it was referred to in Congress as though it had happened, and is still referred to by historians who didn’t check the veracity of the story.

And that brings up the second quality: informational enclaves. Demagoguery depends on people either not being aware of or not believing disconfirming information. The myth of Procter and Gamble being owned by a Satan worshipper (who was supposed to have gone on either Phil Donahue or Oprah Winfrey and announced that commitment) was spread for almost 20 years despite it being quite easy to check and see if any recording of such a show existed. The people I knew who believed it didn’t bother even trying to check. Advocates of the AAS mass-mailing demagoguery (or other fabricated conspiracy stories) only credited information and sources that promoted the demagoguery.

Once the Nazis or Stalinists had control of the media in their countries, the culture of demagoguery escalated. But, even prior to the Nazi silencing of dissent, Germany was in a culture of demagoguery—because people could choose to get all their information from reinforcing media, and many made that choice. Antebellum media was diverse—it was far from univocal—but people could choose to get all their information from one source. They could choose to live in an informational enclave. Many made that choice.

It didn’t end well.