A really smart friend recently asked me about the SF Board of Supervisors Resolution about the NRA. Her question was:

While I think this is a really unhelpful designation that just feeds into the persecuted minority identity I think the NRA likes to use, I’m actually also really interested in this idea of what terrorism/inciting violence actually is. By creating a brand/identity/environment that’s welcoming to white right-wing terrorists, are they effectively inciting violence?

Great question. Technically, four great questions–exactly the questions to ask.

The portions of the resolution (pdf) relevant to the NRA are:

• WHEREAS, The National Rifle Association musters its considerable wealth and organizational strength to promote gun ownership and incite gun owners to acts of violence, and

• WHEREAS, The National Rifle Association spreads propaganda that misinforms and aims to deceive the public about the dangers of gun violence, and

• WHEREAS, The leadership of National Rifle Association promotes extremist positions, in defiance of the views of a majority of its membership and the public, and undermine the general welfare, and

• WHEREAS, The National Rifle Association through its advocacy has armed those individuals who would and have committed acts of terrorism

[…]

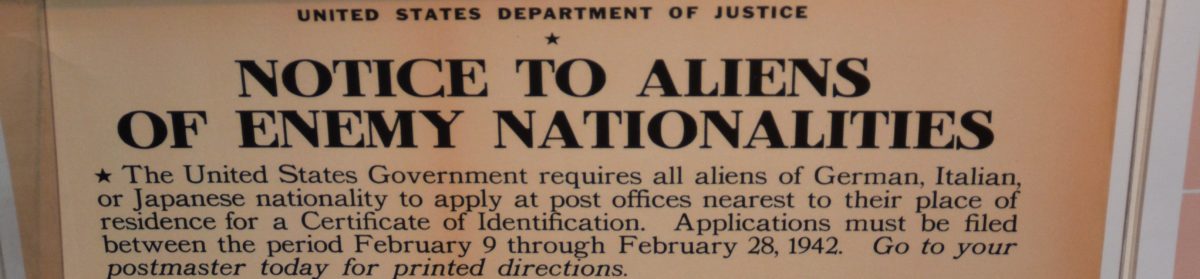

• WHEREAS, The United States Department of Justice defines terrorist activity, in part, as, “The use of any…explosive, firearm, or other weapon or dangerous device, with intent to endanger, directly or indirectly, the safety of one or more individuals or to cause substantial damage to property;” and

• WHEREAS, The United States Department of Justice further includes any individual or member of an organization commits an act that the actor knows, or reasonably should know, affords material support, including communications, funds, weapons, or training to any individual has committed or plans to commit a terrorist act…

My friend was really asking four questions: 1) whether this designation contributes to the NRA fantasy of being gun owners being a persecuted minority; 2) whether the NRA is a domestic terrorist organization; 3) whether this designation is helpful; 4) whether the NRA incites violence.

As far as the first, a major theme in NRA rhetoric is victimization (if you want to get pedantic, masculine victimhood). Gun owners (who are dog whistled as white males in NRA rhetoric) are victimized by crime, Obama kicking down their doors and taking their guns (in 2008 and 2012), not being able to own all the guns, criticism. Those claims of victimization are disconnected from actual events, so nothing the SF Board of Supervisors could make NRA’s base supporters feel more victimized. They’ve already got that turned up to eleven.

The question of whether the NRA is a domestic terrorist organization because it supports domestic terrorism is interesting because it points to how vague (perhaps strategically) the definitions of terrorism are. Technically, the NRA does fit the definition presented in the resolution. Of course, the resolution hasn’t presented all the characteristics that constitute the DOJ definition, but that’s typical of how arguments work in our culture of demagoguery: if you can find one characteristic of a definition or historical analogy that the out-group fits, then you can declare them that thing. Hitler was a charismatic leader, so the out-group charismatic leader is Hitler (but not our in-group leader).

We could consider more criteria than the SF resolution does. And it’s still plausible to argue that the NRA fits the DOJ definition.

The other criteria are:

(A) involve acts dangerous to human life that are a violation of the criminal laws of the United States or of any State;

(B) appear to be intended—

(i) to intimidate or coerce a civilian population;

(ii) to influence the policy of a government by intimidation or coercion; or

(iii) to affect the conduct of a government by mass destruction, assassination, or kidnapping;

We are in a world of domestic terrorism, and the NRA is engaged in actions that could argue enable that terrorism, and so, technically, the NRA does fit the DOJ definition, and that’s why the DOJ definition is a bad definition. It’s much too broad, and would mean that, for instance, the truck driver who drove through protestors was a domestic terrorist, and therefore his employer was a supporter of terrorism and could be condemned as such by an over-active prosecutor. What he did was assault (perhaps even attempted murder), and his employers should be subject to civil suits.

This designation of the NRA as a domestic terrorist organization is sheer political theatre (unless it’s in service of arguing that the DOJ definition is too vague), a performance of in-group loyalty that is about looking right rather than being effective. So, as far as the third part of the question, no, this isn’t effective.

People think this kind of political theatre is “effective” because they have weird (and generally false) narratives about political change and how it happens.

This hope that “if we take an irrational stance and commit to it passionately that will have an important impact” appeals to the false narrative that political change happens because an individual or small group stands up and says, “This is wrong.” That makes great theatre, fiction, and movies, but that hope is harder to defend historically. Political theatre, that is, the political power of taking an irrational and anti-pragmatic stance, works very well on behalf of parties in power.

The Birmingham bus boycott didn’t happen because Rosa Parks suddenly one day decided she was done with segregation refused to change her seat. It happened because there was an organization that had made pragmatic plans about how and when to have a boycott. That doesn’t make her individual protest any less brave or important—she risked a tremendous amount, and her actions cost her (and the other protesters) a lot—it makes her protest smart. The Stonewall riots were part of an arc of gay rights political action. Again, they were crucial, and brave and dangerous, but they neither began nor ended the struggle for gay rights. the beginning of a political movement. Martin Luther may or may not have nailed his theses to a door, but what caused the Reformation wasn’t Luther’s standing tall before the Diet—Jan Huss had done the same thing and been killed for it—but that he had important political support. What Luther did was brave and risky, and it worked because he had a movement behind him, not because he engaged in political theatre. Political theatre is effective when it’s part of an effective political movement.

Henry David Thoreau spent a night in jail protesting the Mexican-American war, rightly recognizing it as being a war fought so that slavery could expand. And he wrote a great essay. And no one else spent a night in jail. And he only spent a night. And most people reading his essay don’t even know it was about slavery. There was very little cost to him for this protest—it wasn’t even that bad a jail. His piece had little or no impact on American history until it was picked up much later, the 1900s.

The SF resolution isn’t a Rosa Parks moment. I don’t even think it’s a Thoreau moment. This resolution has no cost for the SF Board of Supervisors. The resolution is demagoguery. And while demagoguery isn’t always harmful, this one might be, but not because it could alienate supporters of the NRA.

It does, however, aid the rhetorically cunning strategy of the NRA to try to get “gun owners” and “NRA” equated. The NRA has a lot of problems, including that it really isn’t a political organization as much as representative of manufacturers. The political base of the NRA is shrinking, so they’re trying to expand it by persuading gun owners that everyone is out to get them—that gun owners face existential threat. The NRA rhetoric is that it represents all gun owners. It doesn’t. It represents a minority of gun owners. Their claim that the world is divided between gun owners who agree with them and people who want Obama to kick down their doors and take all the guns is sheer demagoguery. The NRA’s extremist policies don’t represent all gun owners, even ones who are very pro-GOP and pro-gun, and gun owners aren’t necessarily supporters of the NRA all guns all the time solution to everything.

This leaves the fourth question of whether the NRA incites violence. And that’s complicated. NRA rhetoric has long involved claims of apocalypses that didn’t happen, demagoguery, fear-mongering. (I was going to link to those claims, but I’m really not comfortable doing that–you can go onto the NRA site and go back in their archives or google Obama take our guns). The NRA can’t support its arguments with rational argumentation, and so it doesn’t even try. The NRA never accurately represents opposition arguments.

The NRA isn’t alone in that move. We’re in a culture of demagoguery and an economy of attention, in which our dominant political imaginary is that every side can be reduced to two sides (good v. bad people, aka us v. them), and, therefore, the best way to get vote, donations, clicks, likes, and shares is to say that there are only two options–us or them.

Trump advocated a second amendment solution in regard to Clinton. Anyone who can get two neurons to fire and is not wrapped in a mummy cocoon of ideology knows he was approving of someone shooting Clinton. But here is what is important about what Trump said: had Clinton said there was a second amendment solution to Trump, Trump supporters would have eaten their own heads off in rage. As would have the NRA talking heads. Did Trump really mean it? That doesn’t matter. What matters is that his supporters would have condemned exactly the same behavior on the part of Clinton.

NRA rhetoric is irresponsible, rabidly demagogic, blazingly tribal, voraciously demagogic, and gleefully evasive of what Christ said we should do. That kind of rhetoric, especially when it’s culturally dominant, fosters violence against the outgroup(s) insofar as it encourages people to believe that violence is an appropriate strategy for dealing with every conflict. But the NRA is hardly alone in its demagoguery, and it’s scapegoating to pretend it is.

That’s what makes the SF resolution political theatre, or virtue signalling, or performance of in-group loyalty, or whatever term you want to use. But the NRA condemning the SF Board for engaging in propaganda and sound-bite (sic) political action is such unprincipled in-group factionalism it could make a cat laugh.

The best evidence is that mass shootings are performances of in-group loyalty on the part of people who live in rhetorical swamps that breed toxic masculinity, the disease of notoriety , our culture of rage.

Does that mean the NRA is off the hook for their demagoguery? Not at all. The NRA might not be directly and explicitly responsible for persuading someone to shoot up a temple , synagogue, baseball game, places with women but it is doing everything it can to persuade anyone who will listen to them that the people who do want to shoot up places should have access to all the guns.

Whether the NRA incites violence is complicated, especially given how violent our everyday rhetoric is (as it always is in a culture of demagoguery) all over the political spectrum. But the NRA does enable mass shootings insofar as every mass shooting enabled by a weapon the NRA wants to make sure is easily available is additional evidence for how damaging the NRA is. (And the “we just need to have a more Christian nation and should enact policies” is an irrational stance and a great example of bad faith argumentation.) But that doesn’t make the SF resolution right. We are not in a zero-sum world of politics in which “the other side” being wrong means this side is right.

We are in a world in which we should be arguing policy, not engaging in competitions about who is more loyal to the in-group or arguments about which group is better.

Gun violence in the US is a major problem, and treating this issue as though it’s a zero-sum argument between the two political parties is like the crew of the Titanic making a decision about navigation on the basis of who won the on-board shuffleboard competition.