“When men go to war, they begin by taking action, which they ought to do last, and only after they have suffered do they engage in discussion” (Thucydides, History 39, Lattimore 1:78)

According to the Greek historian Thucydides, in 431 BCE, the evenly-matched city states of Corinth and Corcyra were in conflict with one another, and each decided to try to ally itself with one of the major regional super powers: Athens and Sparta. At what Thucydides calls “The Debate at Sparta,” a Corinthian speaker tried to persuade Sparta to intervene in the conflict on its side, a policy choice that would almost certainly provoke war between the evenly-matched superpowers of Sparta and Athens.

The conflict between Corcyra and Corinth involved yet another city-state Potidea, as well as complicated questions of prestige (Corcyra had been a colony of Corinth), but it didn’t directly involve Sparta in any way. There were not immediate obvious benefits to getting involved, and there were considerable risks. It wasn’t simply that the outcome of a war between Athens and Sparta was impossible to predict with any certainty—Athens was financially stronger, and had a masterful navy, while Sparta had a much better infantry—but it was very possible that any real winner would be their common enemy Persia. Persia had tried to invade the Hellenic region (what we call “Greece”), and had been repelled only because of combined efforts of Sparta and Athens, as well as political instability back home. Were Athens and Sparta to go to war, it’s possible that they would weaken each other so much that the next Persian invasion would succeed.

Given the unpropitious rhetorical circumstances, what persuasive strategies could the Corinthian speaker use?

This book has an openly normative claim: he should make his case through rational policy deliberation. By ‘rational,’ I don’t mean to endorse the conventional notion of “rationality” as a characteristic of an individual, nor is ‘rationality’ defined as the absence of emotion; what do I mean will become more clear through the course of the book. I’ll make my argument in a largely negative way, showing what rhetorical choices various rhetors made, speculating why they made those choices, and then discussing the implications and consequences. What I will argue in this book is that there is a rhetorical trap for policymakers, a trap that has consequences for everyone in the community, and many people outside of it. Rational policy deliberation is hard, and it is not always the most persuasive strategy. If there are a lot of possible policy options, the situation is complicated or ambiguous, a small number of people are suffering from the “ill,” the “ill” is something that will happen in the distant future or difficult to imagine. A rhetor’s preferred policy might be particularly difficult to present persuasively for many reasons, such as that rational deliberation would show it to be a harmful, dangerous, or meretricious plan. It might be a good policy, but not obviously good, or there might be considerable immediate costs and only long-term benefits. It might be—like several policies discussed in this book—one with high political costs (e.g., one that touches a ‘third rail’).

When rational policy deliberation seems risky or less persuasive, rhetors are tempted to evade it, and that is the trap. They might instead opt for strategies more likely to be effective in the short-term at mobilizing support, selling a product, inspiring voters, gaining assent to a policy, diverting attention from a failure or scandal. For instance, a rhetor might insist that there is still only one choice in terms of available policies, that this choice isn’t just right, but obviously the only possible choice, and therefore we don’t need to engage in policy deliberation at all. We just need to commit fully and passionately to that option. If we believe strongly enough, we will be successful, so anyone insisting on deliberation is either stupid or corrupt, and just trying to waste our time.

This way of evading democratic deliberation has been aptly called “stealth democracy” by Elizabeth Theiss-Morse and John R. Hibbing. They argue that a large number of Americans believe that there are not genuine good faith disagreements about our policy options. Instead, they believe that there is an obviously correct course of action that should and could be taken. People who argue for other policies are doing so only because they are professional politicians, government employees, and “special interests” who do not look out for the best interest of “normal” Americans. This way of thinking about policy disagreements, it should be noted, presumes a group of “normal” Americans who have the same priorities, values, needs, interests, and policy preferences. It thereby also presumes the presence of people whose arguments should be dismissed, whose very presence is corrupting. Since we can’t argue with them (they don’t really have arguments), any political conflict with them is a zero-sum. Appealing to this perception of political conflict might initially seem to be simply evading the responsibilities of rational policy deliberation, but it’s doing more: it’s demonizing deliberation itself.

That perception baits the trap for framing a policy disagreement as an apocalyptic war of extermination. Another strategy for evading deliberation is to insist that there is an Evil and powerful out-group determined to exterminate the in-group, and this policy, party, or leader is our only choice. When people feel threatened, we are less likely to insist upon rational deliberation, so one way a rhetor can avoid having to deliberate rationally is to make an audience believe they are threatened. Since we are faced with imminent extermination, we must act now, and deliberating about our options is suicidal. And so rhetors often claim that we are already at war—real, metaphorical, spiritual, economic, political—and therefore we have to abandon normal ethical standards and political processes and exterminate the Other in preventive self-defense.

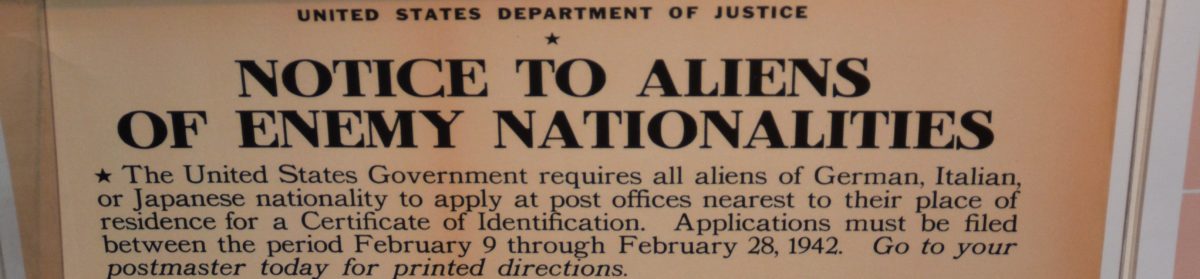

The more that there are rhetors saying that we are justified in going to war against that group because that group is essentially committed to our extermination, the more that we are committed to a war of extermination against them. The more that we are committed to a war of extermination, the more that we are endorsing the abandoning of all the norms of a civil society—the notion that simply being human means you are guaranteed certain rights, regardless of who you are—in favor of an authoritarian society in which there is only the “right” to be in-group. Paradoxically, then, the claim that “they” are already engaged in that war is used to rationalize exterminating “them” and abandoning the notion of universal rights. Communities committed to democratic deliberation have often tried to restrict this understanding of conflict as a war of extermination to foreign policy—how we treat some Other nation. Treating conflict as a war of extermination that prohibits policy deliberation eventually, and inevitably, democratic deliberation.

Rhetors don’t necessarily fall into this trap because they’re stupid or corrupt—these rhetorical strategies don’t seem like traps, or rhetors think they’ll be able to get back out, or they think that’s just how politics works. In this book, I want to show why smart people get trapped, what it means for policy deliberation, and how we dismantle the traps.