I hope I’ve been clear that I believe that politics is about policy—that politics is the realm in which we deliberate about what policies we should pursue, as people in a shared world (what Hannah Arendt called a “common” world). Those policy options are not a binary, and our commitment to any policy shouldn’t derive from our loyalty to our in-group. Effective public disagreement about our policy options doesn’t require that we argue dispassionately, calmly, decorously, or with any particular feelings (such as respect) toward everyone else involved in the argument.

A model of public disagreement that says we need to be calm and respectful toward others is a model that assumes that people don’t really disagree, or don’t really care. That’s a bad model.

We should think about politics, all politics–the politics of our job, club, church, HOA, state, country—as the space in which we try to respond to the fact of legitimate disagreement.

Unhappily, perhaps the most common way of responding to that fact is to deny that disagreement is legitimate. This view says that our political problems aren’t complicated, that the correct answer to the problem is obvious to any reasonable person.

This assumption quickly leads to motivism and arguments for disenfranchisement.

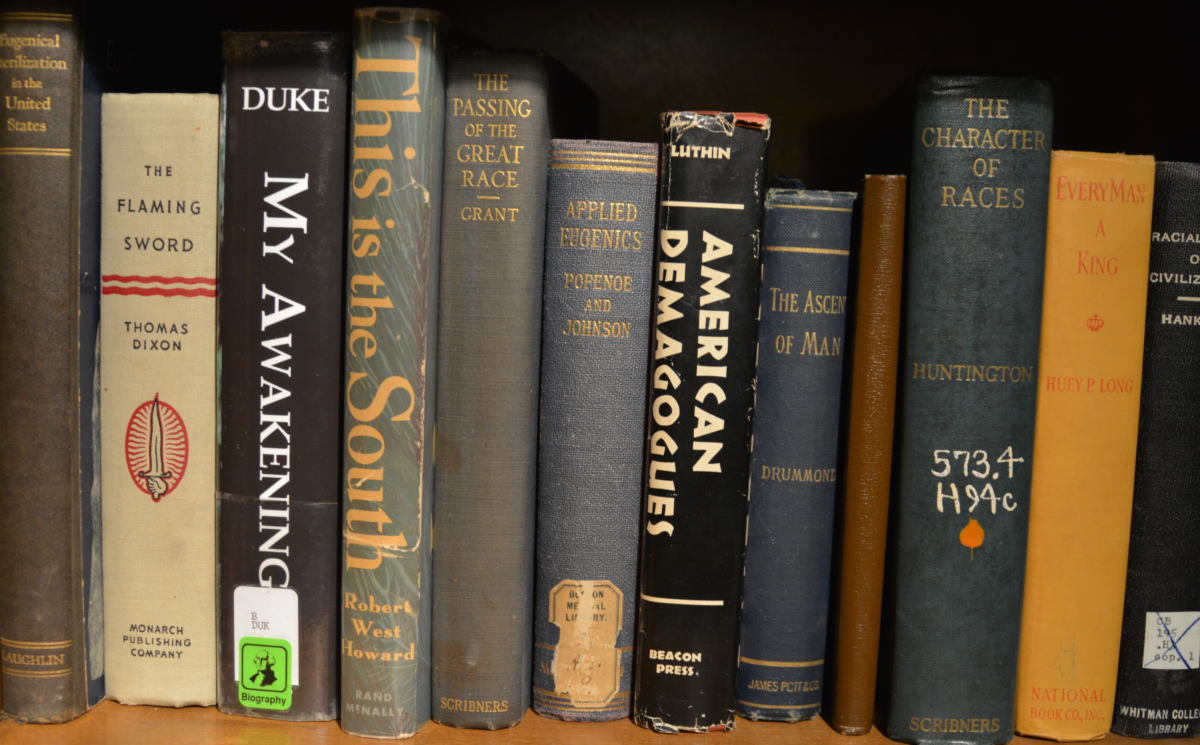

It eventually leads to fascism or authoritarianism of one kind or another.

People genuinely disagree because we genuinely have conflicting interests and values. In addition, we all have limited perception, and therefore none of us can see an issue from every possible perspective. We disagree because each one of us is always at least a little bit wrong. We disagree because we reason differently. We disagree because we really disagree. And yet there is a we—a people whose lives are infinitely entangled, a we that includes people we don’t know, and might not have been born. In politics, the we of our policy decisions is not the we of our in-group.

So, the first rule of effective democratic deliberation is that it acknowledges that disagreement is inevitable and potentially productive.

This isn’t to say that all points of view are equally valid, nor that we are prohibited from being angry and judgmental about points of view with we disagree. It’s fine (even good) to be angry with people who disagree with us. Someone who is openly angry isn’t necessarily making a more irrational argument than someone who appears to be calm.

An apparently calm person isn’t necessarily making a rational argument, and a person who is angry isn’t necessarily making an irrational argument. The rationality of an argument is most effectively determined by the ways the claims fit together, are defended, and how they related to the argument(s) to which it claims to be a response.

The second rule of effective democratic deliberation is that we do not assess arguments on the basis of the affect of the people making the argument.

If we say that disagreement is legitimate, and that we aren’t going to dismiss arguments on the basis that some interlocutors (as they say in argumentation theory) are emotional, then on what grounds are we going to assess arguments?

And here I want to point to the fact that our common notion of political deliberation is poisoned by the false sense that you either believe that the truth is obvious or you are a rabid relativist. It is not obvious to you in the morning whether it will rain, but you do not therefore believe that all points of view regarding the weather are equally legitimate.

Our world, from the mundane (what will traffic be like on my way to work) to the global (what would the consequences be of this trade policy), is not a world in which we are either certain or clueless. We live in a world of probabilities when it comes to the weather. When it comes to the weather, we do not think that a person is either certain or clueless about it. Most of us manage to understand that an 80% chance of rain is not a statement that it will rain (although many people do manage to misunderstand that). We can make a judgment about what to wear even though we recognize our information about the weather is uncertain. Our judgment might be wrong.

The third rule of effective democratic deliberation is that we understand that the correct answer is not obvious–because we are in a world of uncertainty, but acknowledging uncertainty doesn’t mean being unable to judge.

Being uncertain doesn’t mean being indecisive. I can’t be certain that I’m picking the best outfit for the day, but that doesn’t mean I spend eternity naked in my closet. We spend most of our lives in uncertainty and still manage to make a decision about how to get to work (that might be wrong), apply for a job (that might be terrible), go out on a date with someone (which might be disastrous), buy a taco.

The problem is that a lot of people manage that uncertainty by denying that they are uncertain, and when they get evidence that they made a bad decision, they don’t admit the error, or don’t take responsibility for it. And then they can’t learn from their mistakes.

If I decide to wear a shirt that has to be dry cleaned on a hot day when I know I’ll sweat a lot, I not only have to admit it was a mistake, but then I should think about what went wrong with my decision-making process, especially if that same mistake happens repeatedly.

People felt certain that Christians should support slavery, segregation, criminalizing homosexuality. They were wrong.

The fourth rule of effective democratic deliberation is that feeling certain that you are right doesn’t mean you are. Certainty is more often affective than it is cognitive.

Slaves felt slavery was wrong. They were right.

Feeling that you’re right, believing that a source is true or objective because it rings true to you, feeling certain, having seen evidence with your own eyes—none of those things necessarily mean you’re right, but they might. Feelings are something about which we can argue. Defenders of slavery refused to consider the feelings of slaves, while they spent a lot of time talking about their own feelings. The problem with the argument about slavery wasn’t that it was a feelings v. reason argument, but that only some feelings were considered valid.

The whole point of the weather example is that the world in which we live is not one that is one that legitimates someone being cognitively certain. The sense of being certain is an affective choice—people feel certain. And that feeling of certainty is not necessarily the consequence of evidence.

Acknowledging that we are in a world of uncertainty doesn’t mean we’re in a world in which we have to think all points of view are equally valid. But it is a world in which “This claim must be true because I feel certain it’s true” is not actually a good argument.

This is a very fallacious appeal to authority, the false authority of personal conviction. That a person feels certain about something doesn’t mean it’s true; if they feel certain that their memory of an event is accurate, that’s a datapoint. But that evidence has to be assessed like any other piece of evidence, and one of the things we should consider is whether, on the whole, this source is reliable. Feeling certain is a feeling, and so it should be argued about just as much as we argue about other feelings. And we should argue about feelings—our policies should be grounded in our feelings about future generations, our fears, our hopes—but that someone has a strong feeling doesn’t end the argument. That someone feels certain doesn’t end the argument as to whether they’re right.

The fifth rule of effective democratic deliberation is that we are willing to argue about and with feelings, and that feelings don’t end the argument, including the feeling of certainty.

All political arguments are grounded in and usefully informed by feelings. People who wear “fuck your feelings” t-shirts feel strongly that anyone who disagrees with them is wrong. They also think that criticisms of racism, sexism, sexual assault, sexual harassment, ableism, and so on (what they call “political correctnss”) are grounded in the notion that those things are bad because it hurts someone’s feelings. That’s because they live in an informational enclave that inoculates them against what arguments about sexism and racism and so on are actually about.

So, is the “fuck your feelings” about feelings not mattering—an odd claim since the people wearing it feel strongly—or is it saying fuck your feelings? Those t-shirts say their feelings matter; yours don’t.

Either feelings matter or they don’t. When people argue that only the feelings of some groups matter (or only the experts of some group, or the policies of some group), then they arguing for abandoning democracy. Those are all arguments (or assumptions) that only one group really counts. That’s a common way to think about disagreements (and communities), and it’s a bad one.

It’s a way of denying legitimate disagreement that hurts communities in the long run, but seems to provide a kind of solidarity in the short run, and it makes people feel better about themselves (by pretending that “everyone” thinks the same things they do). A better strategy is to hold everyone to the same standards—everyone has feelings, and we can argue with and about them.

The sixth rule of effective democratic deliberation is that we argue together by holding one another to the same standards.

Holding one another to the same standards isn’t saying that we think all arguments are equally valid. Nor does saying that you might feel certain and yet be wrong mean abandoning judgment entirely.

It means that we need to think about ways of making and assessing arguments that aren’t just about whether a claim seems true to us. It also doesn’t mean that we decide an argument is true because it can be supported with evidence that’s true. “All cats should be killed because these cats did a bad thing” is an argument with evidence, and the evidence might be true, but it isn’t a reasonable argument. It isn’t a reasonable way for us to argue because none of us would apply that standard—kill all members of a group because some of them did a bad thing—to our in-group. It is not a way of arguing that any of us would consider valid if applied to us. Therefore, we shouldn’t apply it to others.

We all think that we are reasonable, and we can all find evidence to support what we believe. That’s how motivated reasoning works.

That you believe your beliefs to be reasonable, that you can find evidence to support your beliefs, that you can point to experts whom you believe to be reasonable who say you’re right—none of that actually means your beliefs are reasonable.

Instead of trying to figure out if we’re right by looking for evidence that supports our position, we need to ask ourselves if we would know if we were wrong. Are our beliefs falsifiable? In other words, what evidence would make us change our minds? Are we getting information from sources that tell us when they’ve been wrong (because all media make mistakes)? Are we getting information from media that represents all the positions, especially opposition positions, fairly? Are we getting information from media that would tell us if an in-group member behaved badly or an out-group member was right?

The seventh rule of effective democratic deliberation is that we have to work to make sure we’re getting information from various perspectives.

A common mistake that people make about sources is to think that sources are either “biased” or “objective.” There are more and less reliable sources, but the whole concept of bias is indefensible. We are all biased. We think, act, feel, and believe within a world of cognitive biases.

Being biased and being rational aren’t mutually exclusive. And that we are biased doesn’t mean we’re incapable of rational policy argumentation. A rational approach to argument means acknowledging the ways our biases might be influencing us, and that’s why we have to try to perspective-shift, to look at our claims from the perspective of others. Would we think this a good argument if made by an out-group? Would we consider this a good way of arguing if made by an out-group?

If not, then we need to stop making that argument, or admit it isn’t valid.

Notice that I’m talking about the validity of arguments being determined by standards that apply across all arguments. That’s what makes rational argumentation. Rational argumentation isn’t argument on the part of people who are rational, nor is it argument that has certain surface features. It’s about how people treat one another.

The eighth rule of effective democratic deliberation is that the fairness rule applies to how we assess the validity of arguments.

One common way that people think they’re being rational when they aren’t is when they’re engaged in a fallacious version of argument from authority. People have a tendency to reason by in/out-group membership. One of the consequences of our world is that there is always a study published in a journal that claims to be peer-reviewed and written by someone with advanced degrees that is unmitigated bullshit. Academic reviewers who are doing their job as reviewers appropriately don’t just argue for publication of arguments they think are true, but ones they think are worth arguing about. So, that something is published in a well-respected journal doesn’t mean everything it says is true.

And then there are journals that are “peer-reviewed,” sort of, in that, if you pay enough, you can get peer reviewers who will approve your article. There are also journals associated with an organization with a political agenda that will only publish articles that promote that agenda, such as the Family Research Association. That something is published in one of those journals doesn’t mean it’s true. Nor does it mean it’s false.

It means that studies should always be considered critically.

The ninth rule of effective democratic deliberation is that we have to understand that an argument being published in a journal claiming to be “peer-reviewed” doesn’t mean it’s true. It just means, at best, that it’s worth arguing about.

I’m arguing, passionately, for effective political deliberation grounded in rational policy argumentation, and I’m not saying that feelings should be excluded from political deliberation, especially not the feeling that you’re right.

We should feel we’re right. We should feel passionately that we’re right. Political activism (from voting to knocking on doors) requires believing that we’re right.

But believing that we’re right doesn’t require that we think that our position is the only one that should be considered—that anyone who disagrees with us is evil and should be shunned. What I’m saying (and it’s what a lot of scholars and thinkers about democracy say) is that democracy requires the conviction that you are right so deep that you act on it, with the mental caveat that you might be wrong such that you don’t kill, expel, or disenfranchise everyone who disagrees with you.

Authoritarian systems say that only this political stance is valid, and all others can be silenced as not legitimate political positions, and therefore argumentation is a waste of time. They might engage in trolling, propaganda, demagoguery, but the last thing they will do is engage in argumentation in which all parties are held to the same standards of argumentation.

People who support authoritarian systems don’t see themselves as subverting democracy. They see themselves as promoting true democracy. They believe that politics isn’t an issue of policy, but identity. They believe that there are people who are really the people, whose views really count, and a true democracy is a political system that entirely and only promotes the interests and policy agenda of those real people.

Since these people tend to think in binaries, they think that, if you aren’t as authoritarian as they are in favor of their group, you have no values at all.

Democracy isn’t about what group you’re in; democracy is a world of policy argumentation.

The tenth rule of effective democratic deliberation requires that we understand that there are ways of arguing that contribute to determining the life of our common world, and those ways of arguing operate across political positions.

Authoritarian politics says that there is only one group should have political authority because only that group really represents the interests of “the people.” States that practiced race-based criteria for voting were authoritarian and not democratic (with “the group” being a race); states that are gerrymandered are authoritarian and not democratic (with “the group” being one party).

Authoritarian politics says that it’s legitimate to deny voting rights to various groups because they don’t have the authority to make political decisions.

A person, or group, arguing that there are only two sides to our political world, and that “the other side” is entirely bad is engaged in a damaging kind of discourse, one that’s bad for our community, and bad for our common world getting to good solutions. I’m not saying they are bad, that they should be denied a voice or vote, that our world should be cleansed of them; I’m saying their way of arguing is bad.

I often find myself getting into confusing arguments on this point, partially because some people can only think in terms of identity, and so they can’t distinguish between being the two very different claims: you are a bad person; you are making a bad argument. Good people make bad arguments, and bad people make good arguments.

There are people we believe are bad, who are making what we consider terrible arguments. It’s fine for us to think some people are bad, and it’s fine for us to think (and even say) that some arguments are dishonest, ignorant, incoherent, stupid, evil, and so on. But, if we think that all arguments other than ours are dishonest, ignorant, and so on, then we’re in the realm of demagoguery. It’s damaging when we think the political realm has only one legitimate position in it (ours) and that every other position should be silenced.

I’m saying that effective democratic deliberation has people who disagree deeply, profoundly, disrespectfully, sincerely, and yet can find ways to argue together.

The eleventh rule is that we understand that we are arguing together with people with whom we passionately disagree and might even think are total jerks.

We might think the other people are jerks because they are jerks, because we disagree with them deeply, or because our sources of information have inoculated against even listening to them, and we’re projecting jerk arguments onto people who might have a point of view that would benefit us to hear.

We are not actually in a world polarized between the left and the right; we aren’t even in a world that is on a continuum between the left and right. We are in a world in which our media—ranging from some rando person’s youtube channel to MSNBC—has learned that you don’t get viewers by promising a nuanced explanation of the complicated range of options we have available to us in our vexed situation. You get viewers by simplifying issues, engaging in demagoguery, and making media a prolonged two minutes hate.

The twelfth rule is that we are not in a world of only two options on every issue, and the political realm is not a zero-sum battle between two sides.

I mentioned earlier that we are all prone to cognitive biases, but we aren’t hopelessly trapped by them. Two particularly important biases for thinking about effective democratic deliberation are in-group favoritism and confirmation bias. Our first impulse is to hold our in-group to lower standards than any out-group because, oddly enough, we believe our group is better. So, if an in-group President issues a lot of executive orders, he’s decisive; an out-group President who does exactly the same thing is a fascist authoritarian.

Another really interesting way that in-group favoritism comes up is in whataboutism, the moment that says that it’s okay for an in-group political figure to do this because an out-group political figure did it.

That can look like a fairness argument, but it isn’t. Fairness is about holding all groups to the same standard. Whataboutism comes from the weird accounting in zero-sum binary politics.

Whataboutism says that any bad in-group behavior is erased by finding any similar out-group behavior. Fairness is asking that all groups be held to the same behavior; whataboutism is about vengeance. It’s the way you argued when you were ten: you were justified in borrowing your brother’s bike without asking because he took your basketball without asking six months ago; he says he was justified in that because you took his mitt without asking a year before that; you were justified in borrowing his mitt because three months before that he borrowed….

In a culture of demagoguery, every argument is about how the in-group is better than the out-group.

In the world of effective democratic deliberation, fairness means that your in-group bad behavior isn’t justified because an out-group member did it too. It means you condemn that behavior regardless of group membership.

The thirteenth rule of effective democratic deliberation is that we value fairness across groups over in-group favoritism and confirmation bias.

These rules don’t guarantee good decisions, or even good processes, but they are ways that tend toward better processes.

There aren’t two sides on abortion. There aren’t two sides on gun control. There aren’t two sides on immigration. There are far more than two. But reducing a complicated issue to two sides is politically useful—as Hitler noted, it’s easier to persuade people if you make issues very simple, and as people have noted about Hitler’s rhetoric, that’s most effectively done by reframing the policy issue as simply one instance of the war between Us and a common enemy (Them). That reduction of complicated issues to “us v. them” is appealing to people and therefore profitable for media.

There aren’t two sides on abortion. There aren’t two sides on gun control. There aren’t two sides on immigration. There are far more than two. But reducing a complicated issue to two sides is politically useful—as Hitler noted, it’s easier to persuade people if you make issues very simple, and as people have noted about Hitler’s rhetoric, that’s most effectively done by reframing the policy issue as simply one instance of the war between Us and a common enemy (Them). That reduction of complicated issues to “us v. them” is appealing to people and therefore profitable for media.